Chapter XV: PILGRIMS' PROGRESS.

"Come, and with kindly gifts return homeward again!" --THEOCRITUS, Idyll XXII.

The reason why the peacock was chosen as the earthly symbol of the Prince of Angels has been discussed many times by the pundits, and M. Lescot, in his book recently [137] published about the Yazidis in the Jebel Sinjar, has summed up the somewhat negative result of their deliberations.

Here I was, within stone's throw of a sacred peacock, and yet I decided not to appear conscious of its presence. A qawwâl led us up a narrow street and took us into the crowded courtyard of one of the larger houses of the village. Chickens scratched about the feet of the men standing in the courtyard, some of which, no doubt, were awaiting their turn to visit the sacred bird. The peacock was in a room off the courtyard: I saw arrivals conducted to the door by a qawwâl.

Upon the iwân, or open dais room, sat the mîr, and on benches spread with carpets round the three walls were a number of visitors, two of whom got up to give place to myself and Jiddan. Amongst these one or two wore European coats and the 'Iraqi sidâra, tokens of the townsman and official, and opposite to the mîr sat the local Jacobite priest in his black robes. The Baba Shaikh and his son were also present, so that both spiritual and temporal lords of the Yazidis were met under one roof.

Said Beg, Prince of the Yazidis, Wansa's husband, is a tall and not ill-favoured man of under forty, who wears his very long black beard curled into a lovelock. He gave me a courteous reception, telling me that I had been awaited for some time at Shaikh 'Adi. I explained the reason of my delay and thanked him for his offer of hospitality there, for he had most kindly placed a guest-room there at my disposal. He said that he had given orders that I was to be shown all that was to be seen there (my heart leapt joyfully at this), and that all should be done to make my stay comfortable, and again I thanked him for his hospitality and forethought. Conversation lapsed into polite banalities, and was punctuated by questions about our stay at Baashika by the priest who sat beside me. The coffee ordained by [138] laws of politeness was brought and swallowed, and then, as the morning was already wearing on, I asked permission to take my leave. The mîr wished to send two men with me as escort, but as there was no room for them in the Ford, a compromise was arrived at. A feqîr sent his son, a handsome lad with clear brown eyes called Hajji, who contrived to squeeze himself in between Jiddan and Mikhail at the back amongst the luggage, while I surrounded myself with smaller objects in the seat by the driver, `Aziz.

The road follows the foothills, and tall yellow flowers stood like candelabra above the young corn. Some of the fields were brown and unsown, left fallow till another year. Storks were searching amongst the furrows. In the cornfields I saw plenty of the gay flower called getgetek, which has a flax-like leaf and a pink flower not unlike campion. After passing the mounds of Tepe Gaura and Khorsabad, names familiar from objects in museum cases, we came to the village of Fadhiliyah set in olive-groves to the right of the track. Here a horse and ass yoked together were ploughing the rich brown soil, the plough being of course the simple Virgilian ploughshare which can be shouldered at the day's end by the ploughman and carried home. We continued to follow the line of the foothills, just below them being a flaming yellow carpet of flowers, perhaps hawkweed.

The next village was Nowera, set on low hills to the left, a heap of mud houses with flat roofs rising one above the other like steps and topped by a large prosperous-looking white house at the summit of the mound. It was just here that the road from Baashika met that from Mosul to Shaikhan (or 'Ain Sifni: the town has two names). Cultivation stopped at this point and the ground on either side of the road was brilliant with wild flowers. It climbed upwards, and at the top of the ridge we beheld blue hills, and behind these a [139] mountain-range tipped with snow. The road now switchbacked up and down, and at each rise the hills were closer. Always there were flowers: hawkweed, ranunculus, grape-hyacinth, and a handsome lavender-coloured bindweed, the folk-name of which is liflâf.

The telegraph poles marched with us, for 'Ain Sifni is linked now with the outer world, and on the wires the bee-eaters perched, or swooped in flocks overhead uttering high, gossiping, chirruping calls. These jewel-like birds, all emerald and flame, arrive later than the storks and swallows. In these parts the bee-eater is called tîr gulê, the "flower-bird", because it comes with the flowers.

We passed a village on the right set on a hill all sealing-wax red with ranunculus. I noted many wild flowers here, and saw again that beautiful yellow flower like a rock-rose, the fragrance of which had delighted us in Baashika. Amongst old friends were the lovely hyacinth-blue gladiolus and the white clusters of the Star of Bethlehem, while the iris flourished everywhere. We were mounting higher, and presently, above a stretch of narcissus, now withered, we saw the road winding away to Ba'idri clinging to foothills on our left, and near it but still farther off, would be Al-Kosh, where the prophet Nahum is buried and the monastery of Rabban Hormuzd is cut into the rocky face of the mountain. A man of Tel Keyf told me that in the days before the church on that precipitous rock was rebuilt, it was whitewashed by the monks with lime and milk "and," said he, "the shining light of it was like a diamond, it could be seen as far as Mosul."

The car was now approaching 'Ain Sifni, also set on a hill, and above it like a beacon stood the tall white cone of a Yazidi mazâr. The townlet contains a mixed population of Moslems, Christians, and Yazidis. Below the houses were groves of trees, grassy slopes, and masses of buttercups.

[140] Up the steep slope we rattled. Workmen were busy on the road, which they were transforming into a tarmac highway, so as to link 'Ain Sifni permanently with Mosul, for at present it is often isolated for weeks during the winter rains.

We drew up before the Serai, the Government offices. Here my instructions were to ask for one Sa'adat Effendi, and to call upon the qaimaqâm. I found the latter dignitary sitting in state and coolness in the shade of a great mulberry-tree, smoking and conversing with friends. He had been informed of my coming and received me with dignity, introducing me to several local functionaries, including the schoolmaster, whose intelligent face and charming manners augured well for 'Ain Sifni.

When I asked if the pack-animals ordered for me had arrived, it seemed that the matter, which was not pressing, could be settled later. We drank coffee under the mulberry-tree while I sought news about the war, for the qaimaqâm has a radio: in fact, the place, compared to Baashika, was a very metropolis.

After coffee ("No hurry, no hurry! you have plenty of time!") tea was brought in glasses, and then the schoolmaster, whose two children, a son, Wisam, and a shy little daughter, peeped at me from the protection of their father's knee or arm, took me to the small schoolhouse. Here he and two assistants teach the youth of 'Ain Sifni the three R's, and the classes, though not yet the class-rooms, constantly grow bigger. The Yazidis, he said, here as at Baashika, were at first averse to sending their boys to school, for the Tree of Knowledge bears forbidden fruit, and only shaikhs may read and write. But this prejudice is weakening, and the number of Yazidi pupils increases.

We got back to the mulberry-tree and I asked if the mules had arrived. The inspector and qaimaqâm replied that, unfortunately, they were out in the fields, [141] working. Had they not had word from Mosul of my coming that day? Yes, indeed, but nothing so very definite.

"However," said they, "why do you not go on by car? Everyone goes there by car."

Now years before I had twice been to Shaikh 'Adi by car, without luggage, in dry weather, and each time I had marvelled at the arrival of the car more or less intact. The road is unsuitable for cars even in a country where cars, especially Fords, will set out gaily over roads which can only be so called by a robust effort of imagination. I replied that 'Aziz, our driver, who knew that the road from 'Ain Sifni was evil, had only consented to take us this far on the express condition that he went no farther, the said 'Aziz having newly paid, or borrowed to pay, sixty pounds for his second-hand Ford, and cherishing it like his paternal uncle's daughter. Perhaps, they said, hopefully, another car will turn up. It did not seem likely; moreover, I wondered if, even now, pack-animals might not be procured. They played another card. "We will speak to your driver," they said. 'Aziz was summoned, and he stated that he knew that the road was very bad, and that he would not take his car over it.

"But it is not so bad," they reasoned with him mildly. "It has been improved; much improved: work has been done on it and indeed cars go thither very often." To prove their words, a Yazidi car-driver was produced. He introduced himself as a driver of cars and also as owner of the pack-animals which had not appeared. He added his persuasions to those of authority. Smiling and confident, he assured that doubting Thomas, 'Aziz, that the, road was perfect. One, or at most two, difficult places there might be, but it was easy to get a car over or round them, and he himself had often driven to Shaikh 'Adi.

[142] Unwillingly, gloomily, 'Aziz allowed himself to be persuaded.

"I will accompany you and show you," said the Yazidi driver, and when we said there was not a spare centimetre in a car which already contained five people with their bedding and household gear, he said cheerfully that that was nothing, he could hold on outside.

So, amidst sighs of relief from authority, we set off down the track.

"Not so bad," we said to ourselves hopefully, for the first half-mile was certainly not much worse than the track which leads from Baashika. But it soon deteriorated — in fact, it became indescribably bad. We got out and walked, whilst we heard the car labouring, grinding and bumping, appearing at nightmare angles as it negotiated rocks, or landing with a bump or scrape from a crag. I decided as I walked that, firstly, were a Society founded for Prevention of Cruelty to Cars I would join it, and secondly, that I would greatly increase the price for which 'Aziz had consented reluctantly to bear us farther.

It was a Pilgrims' Progress indeed for 'Aziz, with Sloughs of Despond and Apollyons of boulders, but we enjoyed walking. We approached nearer and nearer to the mountains. Occasionally, when the road became unexpectedly better, we mounted again, but regretted it, as 'Aziz, in his bitterness, set his teeth and drove recklessly at bumps and furrows, muttering curses while we held on and murmured, "We will walk, 'Aziz! Let us walk!" or more urgently, "Yawâsh, yawâsh!" "Softly, softly!" just as John Gilpin besought his steed. But 'Aziz's blood was up and he took no notice. "If my car is smashed," he seemed to imply, "you shall be in it."

We came to streams which we crossed by stepping-stones whilst the car laboured through. The valley became increasingly beautiful. Wild flowers we now [143] took for granted, but as well, may-bushes were in blossom, and the oaks on the hillsides were in tender new leaf. On the floor of the valley were paddy-fields, flooded for rice. Beside one stream which we forded a shepherd wearing a small, round felt cap sat taking his ease beneath an oak-tree, a double reed pipe in his hand.

The way now followed this stream and the valley narrowed. Oleanders, not yet in blossom, grew there in profusion. Then the road crossed the stream once more and our faces were turned up-mountain. It was just after this that the car stopped, bogged in a patch of mud. We had just passed the little hamlet of Lalish, and from this point it is barely a quarter of a mile's walk to the shrine, and in any case, the car could have gone little farther. So I left them to unload, then set off alone, Jiddan promising to secure people from Lalish to bring up our gear.

It was delightful to walk up that shaded pilgrims'

way to Shaikh 'Adi. The path follows the stream which rushes

noisily down over its stony bed. On either side rise mountains,

rocky and overgrown with trees. Half-way up I seated myself on

a boulder to listen to the water, breathe in the perfume of the

herbs and wet earth and revel in the greenness and swaying shadows

of the lovely place. There was a sound, and a Kurdish woman and her

daughter appeared who picked their way over the stepping-stones to

rejoin the path to the hamlet below, gazing at me with smiles of

surprise and answering my greeting in Kurdish. On their shoulders

they bore large embroidered pokes filled with loaves of bread.

The man who had spoken to me was a lean little man with a brown face. He told me that, being of mountain blood, he had begged to be sent to mountains; not necessarily his mountains, but any mountains. His superiors were suspicious, but finally offered him a post here with the loss of a stripe and diminution of pay. He accepted gladly and, he told me, gained by it, "for, khatûn, in a town all one's money goes quickly on food and clothes and cigarettes. Here I live almost for nothing and have no needs and save money. The mountains are my home and better than coffee-houses and cinemas and kalabalagh (commotion). I never wish to see the city again." The second policeman, his superior officer, was a genial soul, and, although himself a Moslem, his tact and kindliness have won respect and affection from the Yazidis who live at the shrine. Talking together, we walked on and came suddenly upon an archway of grey stone and, standing beneath it, two of the white-clad, nun-like attendants of the shrine.

The elder was a woman of late middle age, with an expression of singular sweetness and dignity, whose [145] name I learned later was Daya Qoteh. A widow of good family, she had renounced the world and come here, becoming the abbess, or kabâneh, of this small community of white ladies. The other, a girl, was a novice vowed to spend her life unmarried in the service of the holy place. Over their white robes they wore a meyzâr of white homespun wool, and a wimple was wound over their spotless white turbans and brought over the lower part of the face, sometimes covering the mouth. They walked barefoot, as do all Yazidis when in the sacred precincts.

When, later, I sat with them in the forecourt of the temple of Shaikh 'Adi, I saw the third of the white trio, sitting on the wall by their private apartments. I faintly remembered having seen her on a previous visit to Shaikh 'Adi some seventeen years before. Now she was an old, old woman, and her face wrinkled and seamed. Her aquiline nose that curved to meet her chin showed in profile as she sat on the grey wall, her back bent, and twirled unceasingly her spindle as her old fingers detached threads of the white cotton wound round her left arm.

"She is spinning wicks," they said, for spinning wicks for the temple lights is one of the occupations of the holy women.

To me, as she sat there, old and absorbed, she looked like Clotho, spinning the threads of human destiny. Not once did she glance below, though she must have heard our voices unless she had become deaf, nor, during all my stay, did she once approach me or speak. Once I came face to face with her, but she turned back immediately. The fine old face was empty and the old eyes unseeing. They told me that in her age she has become silent and lost of spirit, and does nothing the day long but ply her spindle.

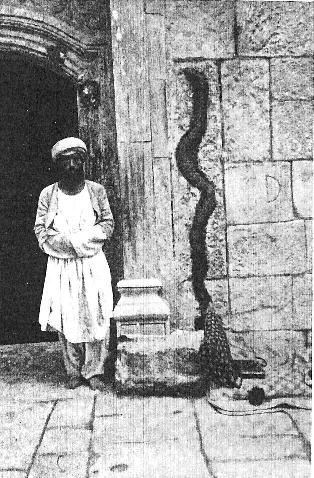

I have gone sadly ahead of events. I was taken by these white ladies and the police by winding ways, [146] under archways and across ancient paved courtyards across which mountain water rushed in paved beds, and past the temple of Shaikh 'Adi itself, where the famous black snake is carved on the long stone by the doorway, down steps and under more archways, until we arrived at the courtyard where on my first visit I had been entertained by guardians of the shrine.

It lies to the south of the temple, and off it are the living-rooms of Faqir Reshu, the kannâs (Sweeper) or Servitor of the shrine. He came forward to meet me, and cushions were laid on a stone platform beneath a pergola of boughs, so that I might rest in its shade while tea was prepared, sweetened tea in small waisted glasses, fresh made over an open fire of mountain wood. His family lived here with him, for, unlike the white ladies and the shawîsh, faqîrs, in spite of their ascetic life, may marry. The kannâs, or ferrâsh as he is sometimes called, acts as Servitor of the shrine for one year only, and pays for the privilege, which is accorded to the highest bidder. Faqir Reshu had paid the mîr three hundred and fifty dinars (£550) for his year's tenancy, and in normal years he might hope to make this and far more out of the offerings of pilgrims who visit the shrine, especially at the great Feast of Assembly in the autumn, when thousands travel to the valley and camp out on the hillsides and in the stone huts dotted over the sides of the valley. Pilgrims give not only money but jewels, gold and silver ornaments, so that the custodian usually leaves the valley a richer man than he went in. But prospects this year of war were gloomy.

His duties are to receive the pilgrims — and their fees — to show them the shrines and particularly the temple and tomb of Shaikh 'Adi, to keep the holy places swept and clean, and, at every sunset, to kindle the sacred lamps and lights. This is by no means a light task. Every evening he uses two mâns of olive-oil in [147] his pilgrimage of illumination, that is to say, thirteen large huqqas, he told me. A mân meant nothing to me, and a huqqa is the vaguest of measures, so I asked Faqir Reshu if he could give me an idea of what a mân was. "A petrol tin," he answered, "contains about a mân and a half."

Faqir Reshu, the Servitor of the year, was a small, lean, sallow little man in type very different from the fair, healthy, open-faced villagers of Baashika. He looked darker, meaner: his pinched face was pale and pock-marked, his eyes were dark and opaque and he rarely smiled. He was a native of Ba'idri, where the mîr lives, but his wife, a buxom, good-tempered girl who had borne him a boy and was now suckling a baby daughter, came from Bahzané. They shared the couple of rooms with another woman, wife of his brother, a faqîr whom I had seen in Bahzané, now touring with the qawwâls and sacred peacock. This woman was stepmother to Hajji, the Yazidi lad who had accompanied us from Bahzané. She, too, had a baby girl. The pair of families ate, cooked and sat in the paved court before their rooms, washing their dishes in a stream which courses down a paved channel near the shrine.

I had hoped much from the letter which Rashid had given me to the shawîsh, the permanent Guardian of the shrine, for he, Rashid told me, spoke Arabic as well as Kurdish, and I was disappointed to find that he, too, was absent touring the villages. It was said that he was a man of knowledge, not only of the faith, but also of the world, and I had hoped to learn much from him. As soon as I saw Faqir Reshu, whose Arabic was halting, I realized that here I should find it difficult to strike a responsive spark, and it did not take me long to find out that he was jealously fanatical by temperament. He was, however, scrupulous about his duties as host, and the scrappy lunch we had swallowed [148] as we went from' Ain Sifni was supplemented later by a meal they offered us in their quarters. It consisted of chicken and rice washed down by shenîna and scooped into our mouths by pieces of thin Kurdish bread.

The guest-room, to which I was conducted by the faqîr, was a light structure built above a stone chamber, a few yards from the baptism tank and a swift stream which moved over a paved channel. To reach my eyrie, which was surrounded entirely by windows — I was glad of Captain C.'s curtains — one ascended steps from the paved way which leads uphill by the baptism cisterns, and came into the large stone court where arches on either side shelter pedlars and their wares at the time of the autumn feast. Then more steps led to an earthen platform shaded by an enormous and very ancient tree, and from this more steps ascended to a small new terrace and the guest-room. This was shaded by a big mulberry-tree. The guest-room was the least seemly thing in the whole warren of buildings and courts, for it had an iron roof, and looked the afterthought that it was. Inside, the rain had stained the walls a little, but there were benches on which one could sit or sleep, plenty of pegs for clothes, and a somewhat dilapidated cupboard with shelves and a glass front of which only a pane or so remained. It was an excellent and unexpectedly comfortable shelter for the traveller, and a palace compared to the ordinary Kurdish dwelling-room, shared with domestic animals.

To have so many windows was delightful. On one side I had rocks and trees, and a rocky path leading to some upper sanctuaries, and from the other windows a view over the complex of ancient courtyards, archways and rushing water, while my few curtains sufficed to screen one side of the room from the men who sat all day on the platform below. Here they played chess on a board traced on the ground with a pointed stick, with acorns, peas, and stones for chessmen: here the [149] police with Jiddan and Mikhail ate the food sent them daily from the faqîr's house, and here, after sunset, they brought large oak boughs and kindled a leaping fire, around which they sat and talked till sleep overtook them. Then they lay down on rugs and quilts and slept round the fire. From one unscreened window I could see the faqîr every evening going his rounds with the sacred fire, and watch little flames leap up as he placed burning wicks here and there on his way. He bore a large bowl of the oil in his left hand. To this bowl a wide lip had been soldered, and laid on this lip, their ends hanging down in the oil, were a bunch of burning wicks. Just before dusk (and light went early because the westerly sun was soon hidden behind the mountains), he set off barefoot on his rounds, carrying his bowl and ladle. Here and there, on jutting corners of masonry or of rock, he laid a wick to burn itself out, and wherever a lamp stood in a niche, he poured in oil and set a fresh wick alight in its lip. At Shakih 'Adi, except in the temple, where square lamps similar to those I had seen at Shaikh Muhammad were used, lamps were of the ancient classical shape, and made of iron. As the Servitor approached with his lights, all stood up and did not resume their seats till he had disappeared up a passage-way or under an arch, to reappear later higher up, either amongst the buildings or rocks.

Again I run ahead of my narrative. My first task, when my new abode had been swept out, was to dispose of the baggage and set up the camp-bed. These had arrived by way of the steep path from Lalish on the backs of villagers, headed by the chauffeur-driver himself, who had the grace to be a little ashamed of having told 'Aziz that the road was so good. 'Aziz himself appeared later on, having pulled his car out of the mud with the help of villagers. He was both surprised and pleased when I paid him a quarter of a dinar more than the agreed price, and we said good-bye on excellent [150] terms, he promising to tell the authorities in 'Ain Sifni that for the return journey I preferred pack-animals, and would not require a car until I reached 'Ain Sifni.

A table had been provided in the guest-chamber and on this I set my wash-basin, but the faqîr looked troubled when he saw our two hurricane petroleum lanterns. "These cannot be used here," he said, "for we may only burn olive-oil." He indicated two tiny lamps like the dim red lights which burn before altars in Christian churches. They contained a spoonful or so of olive-oil and a single wick. Mikhail and I looked at each other in some consternation.

"May wax candles be used?" I asked humbly, and did not mention that the wax was petroleum wax.

After some thought, the faqîr gave permission. We

wondered if he would ban the Primus which we used

as cooking-stove, for that certainly would not flourish

on an olive-oil diet. However, it was never brought

into question. Mikhail erected the Primus in the stone chamber

below and the faqîr turned a discreetly blind

eye in its direction. There was one other inconvenience.

Sanitary arrangements were non-existent,

for none may pollute the holy valley. For necessities of

Nature, the pilgrim must climb out to the pagan hospitality

of the mountain. Nevertheless, I noticed huts used

for stabling in the precincts for mules and horses,

and that no objection was offered if a beast staled or

vented droppings. Cats, too, roamed about the place, as

soft-footed as the nuns, but dogs were chased off as soon

as they appeared. Sometimes they managed to slink up from

the village below, in search of food.

[151]

Chapter XVI SHAIKH 'ADI: THE TEMPLE PRECINCTS

"A right holy precinct runs round it, and a ceaseless stream that falleth from the rocks on every side is green with laurels and myrtles and fragrant cypress." -THEOCRITUS, Epigram IV.

According to a Moslem tradition, Shaikh 'Adi bin Musafir, who died in the odour of sanctity at a great age somewhere about the year 1163 A.D., adopted as a retreat for himself and his disciples a Christian monastery at Lalesh in the Hakkari mountains, that is to say, in the valley where his reputed tomb is shown today, and indeed the place suggests a mediaeval abbey and the atmosphere is wholly cloistral. The three white nuns, turbaned and wimpled, and spotless from head to foot, complete the illusion. They move silently as disembodied spirits, visiting the shrines or else sit plying their spindles, twisting either white lambs' wool into yarn for their mantles, or white cotton into lamp-wicks. Every morning I saw the abbess and her novice setting out in single file on a pilgrimage round the many shrines, devoutly kissing the stones as they passed on their barefoot way. As they returned one day in the early sunlight I noticed that the young novice had gathered a bunch of scarlet ranunculus and set it in her white turban as though she still thought of the spring feast, the wild dance of the debka and the delights she had forsworn for ever.

The programme of their day was governed by the sun: to the sun they turned to pray, and the image of the life-giving orb is graven everywhere on the [152] shrines. Shaikh 'Adi was born towards the end of the eleventh century at Baalbek in Syria, within sight of the mighty ruins which had once held a shrine to, the Sungod. He probably visited the vast temple of the Sungod at Tadmor, then still almost intact. Often must he have passed beneath the portal of the temple of Bacchus at Baalbek, upon which poppies and wheat are sculptured with such tender and gracious skill, preaching the silent text that death is but a sleep and a forgetting, and that the life that is dormant must again, like the corn, press forward to the light. Such memories did the mystic bring with him when he came to this sheltered place of peace where the rigours of winter are softened and spring lingers long.

Nothing that is known about him speaks of anything but orthodoxy, but he was a Sufi, and the secret doctrines of Sufism have always been suspected of pantheism and the Sufi sects of cherishing ancient faiths. It is certain that the successors of his brotherhood, the 'Adawiya, were roundly accused of pantheism and heathenism, and it may be that Buddhist missionaries, passing over the silk road through Persia and the Middle East, gained in the course of centuries secret adherents amongst religious seekers to the doctrines of reincarnation, for not only the Yazidis but the Druzes believe that life on earth is many times repeated.

Jiddan, who took off his shoes the instant he passed the entrance to the valley and went barefoot the whole time of our stay, went at once into the temple (or church), first prostrating himself, kissing the stones and doorway and standing awhile in silent prayer. Then he placed his offering on the threshold stone near the relief of the black serpent. This retains its jet-blackness by being rubbed with a mixture of olive-oil and the black obtained from the smoke of the sacred lamps. To their surprise, I did not immediately visit this most important of all the shrines and pay my respect to [153] Shaikh 'Adi's tomb. I had explored it on two previous occasions and this time proposed to enter it on the last day of my stay. "It is well to keep the best till last," I told the faqîr.

I contented myself, therefore, with examining the building on the outside. It has obviously been rebuilt several times. Not only Moslem, but Christian tradition claims that it was once the church of a monastery, and it is probable that this, in turn, was built on the site of a pagan shrine, for this valley, visited by the first sun and murmurous with many springs, must have been sacred since very early times. To reach the temple (let us therefore call it a temple), one must cross the stone-paved forecourt with arched recesses on either side which I described in the last chapter, pass under a short vaulted way with benches on either side for lying or sitting, and thence descend steps into the court of the temple itself, also paved with grey stone. When the door of the temple is open one can see directly from this dark archway across the court into the interior. Within, the deep gloom is faintly illuminated by the steady light of an olive-oil lamp. The courtyard is fairly large. The archway described above which admits to it is in its north-west corner and exactly opposite the temple-door, guarded by the famous black snake on the upright at the right of the portal. The temple occupies all the west side of the court, and on the large stone wall-blocks are inscriptions and carvings in sunk relief, or rather incisions, some of them obliterated, others clear. In the south wall of the court there are chambers: one, for storing the sacred bread, is protected by a curious representation above the door of lions facing each other with open jaws on a background of dentated ornament. They threw open the door of this room, but I did not enter, for the floor was strewn with bread, and in 'Iraq it is a sin to tread upon bread, which is looked upon as God's especial provision for the life of [154] man. They were pleased at the reason I gave for not going in.

Steps and an archway at the western end of the south wall lead sharply round to the left and down to the lower courtyard where the faqîr lives with his family and guests are entertained. Off these steps, too, a door leads to the private apartments of the white ladies, to an upper room and the terrace upon which I saw the aged nun spinning.

The masonry of most of the whole complex of buildings

is of unmortared stone, shaped, square or oblong,

fairly even and held in place by its own weight. The

blocks of stone are massive but not of unusual size: an

average block is a foot or two in length and a foot or

more in breadth, though the size varies considerably,

some being far larger and others smaller. In the interstices

of the stones are plants and herbs, and between

the paving stones of the temple-court daisies and small

scented irises grow freely.

Had anyone been stung, he had but to repair to the mazâr of Abu-l-'Aqrabi. Dust from this shrine, Hajji [156] assured me, would cure any scorpion-bite if placed at once on the wound, and he took me to see it. It stood on the hillside which rises sheer on the north side of the temple, together with a number of other shrines and small shelters for pilgrims, built of stone and doorless, and looking themselves like natural features of the landscape, lodged as they are on the terraced slopes between rocks and grassy patches sweet with wild flowers.

Close to the scorpion shaikh is the more pretentious shrine of Shaikh 'Abdul-Qadir, not, I suppose, the saint of that name whose mosque in Baghdad is a place of pilgrimage for Sunna all over the world, although that great Sufi mystic was the contemporary and friend of Shaikh 'Adi. This Shaikh 'Abdul-Qadir was "one of the companions of Shaikh 'Adi." Of the other, the more famous 'Abdul-Qadir al-Gailani, a Yazidi told me years ago that there was such communion between his spirit and that of Shaikh 'Adi bin Musafir that if the latter stood in a circle traced by pious magic, he could converse with his friend in Baghdad "just as you talk to each other with wireless."

The mazâr is decorated by a representation of the sun, the inner disc of which contains thirteen petals or rays. Just below the shrine of 'Abdul-Qadir and close to the northern wall of the temple grows an old male terebinth tree, and pilgrims believe that its leaves, placed on the eyes, will heal them and cure discharge from them. The interstices of the northern wall on its outer face are filled with chips of stone and small pebbles.

"If pilgrims place a stone here," Hajji informed us — for Jiddan had rejoined me — "and believe, the wish of their hearts will come to pass."

Jiddan at once picked up a stone and put it in, and I followed suit.

"Must the wish be secret?" I asked.

"No, it is permitted to tell the wish. What was yours, khatûn?"

[157] I told them I had wished for a speedy end to the war and they chorused deeply, "A good wish, by Allah, a good wish!"

Behind the south wall of the temple, as said above, are the quarters of the kannâs, but between these and the temple runs a semi-subterranean passage, below which a wide stone aqueduct conveys a rushing stream downhill. At intervals the paving of the passage is interspaced with square openings showing the water running smoothly below. I followed this passage and came to a door opening on to yet another courtyard behind the temple. Here the water dives below again except where, at one spot, the torrent has been unroofed for drinking and washing purposes. Stacked against a wall here is a vast heap of oak logs, kept here for roasting the flesh of the sacrificial bull at the time of the big autumn feast. This bull, which I had hitherto understood to be white, may be, the faqîr told me, of any colour, and is often black. The bull is led round the shrine of Shaikh Shems in procession with flowers on its head, and slaughtered just below that shrine, so that it is clearly a form of sun-sacrifice. When the beast's throat is cut with the sacrificial knife, the donor of the bull spreads his cloak so that some of the blood may be sprinkled upon it, for this brings a baraka, a blessing, upon him and his. This information I had from Yazidis, but the faqîr denied the cloak, and when asked what was said when the bull was slaughtered replied, "Nothing but 'In the Name of God'." This was obviously untrue, and I know that if I am to find out what happens at this most interesting ceremony, I must witness it myself.

Following round to the east end of the building, and passing a large mulberry-tree, I saw water gushing out below rock and masonry in a waterfall: this may be the outlet to the spring (Zemzem) described by Gertrude Bell and Dr. Wigram as passing through the cavern [158] beneath the temple, although I was unable to verify this. A second mulberry-tree grew here, and steps led up to a large vaulted chamber used as a dormitory by women pilgrims during the great autumn feast. In the eastern wall of this chamber is a hole, and it is believed that if a person, standing some fifteen feet away, extends his arms and hands before him, shuts his eyes and pacing forward blindly succeeds thrice running in thrusting his finger-tips into the cavity without touching the wall itself, he will gain a secret wish. Of course we tried, and of course did not succeed. The wishes of one's heart are not so easily come by.

It was growing late, and I returned by way of the temple courtyard. In it is a cistern of running water in which wooden bowls (shqâfaq) float, and peering into it I discerned in the clear water one of the black and yellow newts peculiar to the waters of the holy valley. These, which when full-grown are some seven or eight inches long, are looked upon as sacred and never killed. With such vivid colouring the creatures should be poisonous, but they assured me they were not.

I bade Hajji and his uncle good night and returned alone through the darkening courtyards and reached my lodging above the noisy water. I heard its never-ceasing voice whenever I woke that night. Otherwise there was deep silence. Even by day the bleating of goat or sheep is never heard in the valley nor the lowing of cattle: it is a sanctuary for squirrels and birds. Above the rush of the water hurrying along its paved path I sometimes heard one cool musical call, like a pearl dropped into the night, or a single note from a qawwâl's flute. I asked what it was one evening, and they answered that it was a bird called totoy.

"The nightingale, too," they said, "sings at night,

but he has not yet come to these uplands."

Chapter XVII: THE SHRINES OF SHAIKH 'ADI.

"Close at hand the sacred water from the nymphs' own cave welled forth with murmurs musical." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll VII.

Lying abed the next morning, I took myself to task for the muddled impression I had received of the whole place. I resolved to get a clear plan of the shrines into my head, to explore the maze of buildings and rocks with method. "The bother is," I excused myself, "that it is all so lovely and unexpected, so intricate and flower-grown, that one is enticed away like Red Ridinghood in the wood and forgets even to make notes, and the result will be that all serious observation of fact will be obscured by the memory of irrelevant small delights."

So, after Mikhail had brought me breakfast upon the sunny terrace, placing the table in the shade of the mulberry-tree, I got out a pencil and my fat notebook, determined to be conscientious. Hajji put himself entirely at my disposal. He knew the shrines and would take me everywhere.

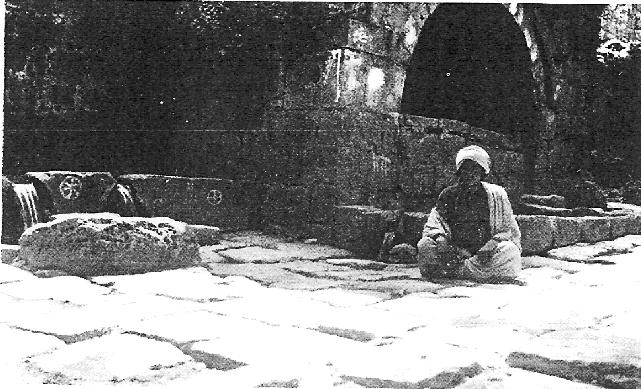

I began with the baptism cisterns. Of two open cisterns, it is the lower which is used for baptism. In both one can see the curious yellow and black newts on the stone bottom. The baptism cistern is filled from above by water which leaves by two spouts, and the centre of its floor is deeper than the sides by a step, so that I presume the baptist, who may be either a faqîr or a pîr, stands on one level, and the person baptized on the other. A small archway, closed by a wooden [160] door, allows water to flow down from an upper chamber, the entrance to which is above. I asked several times about baptism. Only males are baptized in the open cistern. Yazidis, like Christians, go through the ceremony once only, but baptism is not vital to salvation, nor is it looked upon as an admittance to the sect. It merely confers sanctity, purity, and a blessing. It can be performed nowhere else, and if circumstance prevents a person from aver coming to Shaikh 'Adi, he is in danger of no pains or penalties. The ceremony may be performed late in life, but it is the duty of every Yazidi parent to try to bring his children to the holy valley for the rite. The baby, child or youth is divested of all garments and immersed completely three times. The faqîr, or pîr, does not undress, but wears new clothes for the occasion. He does not pray at length, but merely invokes the name of God. (This information from the faqîr is to be accepted with reserve.) A boy pays seventy-five fils (about 1s. 6d.) for his baptism; a girl, fifty fils.

Girls, who are also undressed, are immersed in the closed chamber above. To reach tills, one ascends steps to the left of the tanks, a low door giving admission. Hajji had not the key, so we could only surmise what it was like by listening to sounds of rushing water within. The entrance is surmounted by a worn inscription in Arabic and the seven stones of which doorposts and lintel are formed are decorated by low reliefs which show good craftsmanship. The principal design is a vase with a flower-shaped top, a trefoil or fleur-de-lis adorning the body of the vase which stands on a plain, well-defined stand. On either side of the vase appear handles or lugs resembling stems or branches with floriated ends. A second chamber, also closed, lies above the baptism chamber for girls, for both are built on the hillside. The baptism chambers and cisterns are crowned by a white cone, and the whole is known [161] as Kan Yasbi. Noticeable on the walls of this shrine and of that of Shaikh Shems, to which the steps past the chambers lead, is the prevalence of the cross motif on decorated stone blocks which occur here and there. Opposite the girls' chamber is a very small dried tree to which are tied many votive rags. Women pilgrims beg a tiny scrap of its wood, which they suspend round the necks of their babies, in the belief that it will avert the Evil Eye. Grass, daisies, buttercups, dandelion clocks, and grape-hyacinth crop up between every paving-stone.

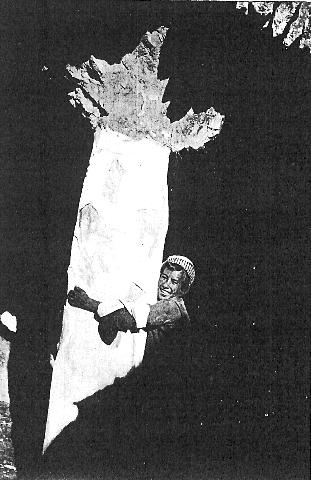

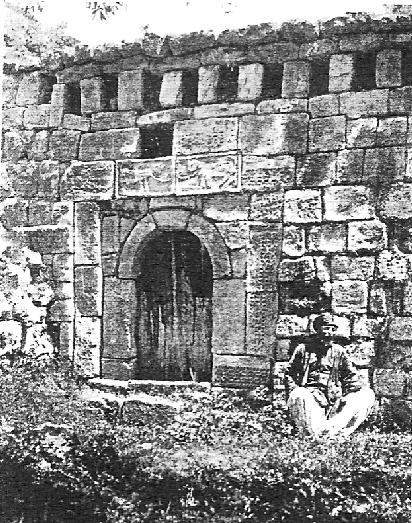

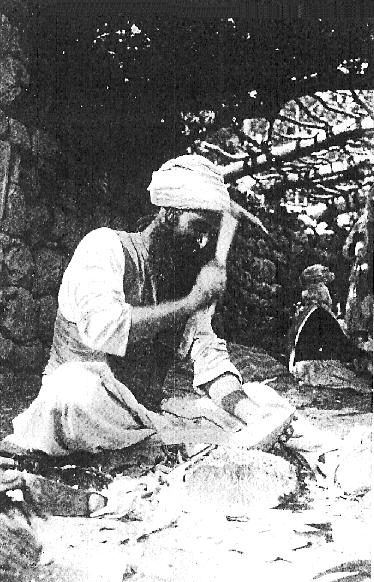

Door to the girls' baptismal chamber.

(Hajji sits by the door.)

The shrine of Shaikh Shems, second in importance only to that of Shaikh 'Adi, is at the top of the flight of steps. I noticed that the official title of the shrine, Shaikh Shems-ad-Din, was little used by the Yazidis, and, indeed, I think that any human "Sun-of-the-Faith" has long ago been eclipsed by the Sungod himself. There was an actual Shaikh Shems-ad-Din, grandson to Shaikh 'Adi's successor, and his full name was Hasan ibn 'Adi Shems-ad-Din. The "of-the-faith" part of the name now provides a convenient Moslem disguise, and Shaikh Shems may be no other than the ancient god Shamish to whom their neighbours in the south, the Mandaeans, still pay left-handed worship. The sun, together with that mysterious Spirit of the Place whose sign visible is the leaping water, are the divinities, or perhaps one should say symbols of godhead, most honoured in the valley. The lion, which appears on so many of the lintels, is a sun-beast, and representations of the sun occur over and over again, accompanied by his sister orb, the moon, and attendant stars.

A portico stands before the shrine-door of Shaikh Shems, and above the latter is incised the likeness of a Yazidi cone-spire, with a crescent moon and star beside it. There are other decorated stones on the wall to the left. To the right of the door a snake in the [162] usual elongated position is carved; on the face of the threshold stone there is a star, and on the wall at the right, a gopâl, or hooked stick. At the entrance of the shrine I removed my shoes, but the tomb within is not worthy of notice. Steps continue up to the flat roof upon which stands the solid base of the fluted spire. The latter culminates in a gold, or gold-plated, ball. The shrine stands much higher than Shaikh 'Adi's, and the ball must catch the first rays of the rising sun when it strikes up the valley.

On the wall going up to Shaikh Shems. (Rope-like border.)

Over the large arch above the first flight of steps to Shaikh Shems.

On side of arch, Shaikh Shems.

The grass and flowery terrace of the next hill level are flush with the roof of Shaikh Shems, and walking [163] off the roof in a westerly direction we arrived at the shrine of the Lady Fakhra. As I have said in an earlier chapter, this saint is the patroness of women in childbirth, and dust from her shrine is helpful to labour if placed under the pillow or drunk with a little water. Barren women put clay made of the dust on their heads when their husbands visit the nuptial couch.

It is a good spot from which to look down the valley, where white spires rise from amongst the leafy woods, while here and there, on the rocky sides of the hills on either side, stand pilgrim huts, or lesser shrines, doorless; the dark arches seen thus in the distance looking like watching eyes. Bees buzzed amongst the flowers, and on the steps grew Solomon's Seal, its creamy bells drooping downward and swaying with the weight of the visiting insects.

The next shrine moving across is that of Nasr-ad-Din. It is a plain vaulted building without either forecourt or cone, or even a doorway. A double arch replaces the latter and a crude lion guards the left and a coiled snake the right of the entrance. It is the only serpent in this position that I saw at Shaikh 'Adi.

A little higher up we came to the shrine of Kadi (or Qadi?) Bilban. Above the entrance is another crude lion, his jaws open and his tail curved over his back, and on either side of it, elongated vertical serpents of the usual Yazidi pattern. The building has a second entrance, also decorated, the carvings including a gopâl. A little downhill to the left is a sacred tree with niches beside it for lamps. Hajji told me that dust from the shrine of Nasr-ad-Din was efficacious for stomach disorders and cured constipation. We had now crossed the head of the flowery valley, and going steeply downhill and crossing by stepping-stones a stream almost hidden here and there by overhanging blackberry bushes, we mounted the hill which rises on the north of the valley.

[164] Here there is a cavern in the rocky face, and we entered it, for, said Hajji, it is a shrine especially visited by women. In the middle of the cavern is a pillar coated with cement and whitewashed. Whether this phallic object was originally natural rock or not, I did not discover. Women embrace it with both arms, endeavouring to make their finger-tips meet, and pray if barren that their wombs may be opened, or if unwedded that a husband may soon remove their virginity. Each suppliant brings an offering with her, and when her wish is granted she makes a gift in token of gratitude. The cave, or rather the pillar, is called Ustuna Mradha.

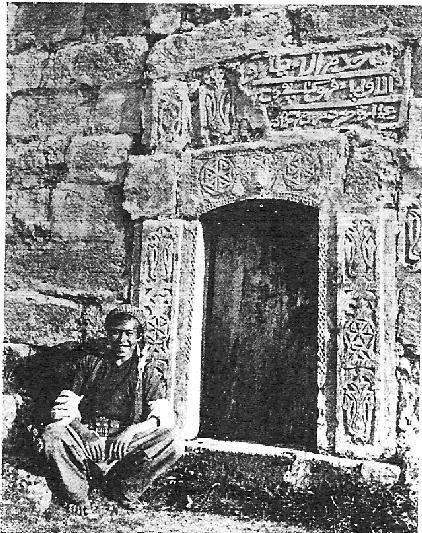

The phallic column in the cavern of Ustuna Mradha.

Close by, on the same hillside, is an oblong chapel the shape and construction of which differ considerably from those of other shrines. The blocks of which it is built are carefully shaped, and at the top it is ventilated by small blocks set endways at regular intervals. There is no mortar between the stones, and they are so well-cut that they lie even. Above the door there is a low relief of two chained leopards facing each other, and on one of the doorposts is a design portraying a chain. This is the shrine of Pir Hajjali, whose peculiar power it is to cure the distraught. Dust from this shrine mixed with water from the sacred springs, when placed upon the head, is thought to recall the wits of those whose minds are wandering, and obstinate or violent cases are brought here and chained inside for a night or so until the saint drives out the spirit of madness which possesses them.

(Faqir Reshu sits by the door.)

Another shrine, also on the northern side of the valley, is called Shaikh Simail, but I was unable to elicit clearly the medicinal value of dust from this spot. Hajji murmured something about hâwa, "wind," which is a generic name for all bodily pains, whether caused by flatulence, rheumatism, or pneumonia.

[165] I went presently on some errand to Mammeh, the faqîr's wife, in her quarters. In the courtyard I passed two other lodgers in the shrine, one a Yazidi lad of twenty, probably related to the faqîr, the other a shaikh, brown-bearded and gentle, a very likeable person. He was usually to be found on the pavement under the pergola chipping away at a piece of wood, for he manufactured spoons from the oakwood which the valley provided. Spoons coming from so holy a place are greatly valued by pilgrims and others, and the shaikh travels round Yazidi villages with them, or gives them to pilgrims, receiving in exchange a gift of money, or a sheep or a goat, or even a chicken. These are not payments, but return gifts, and in such manner, it seemed, the shaikh contrived to make a living. When I returned to Baghdad I was the possessor of one of these spoons, embellished by a carving made by one of my policeman friends.

Later in the day I received a visit from two of the white ladies, Daya Qoteh and Daya Rozeh, kabana, or abbess, and novice respectively. Both arrived with their spindles in their hands. Daya Qoteh had a skein of white lambs' wool over her arm, the novice was twisting strands for wicks. I had to call in Jiddan to translate, as they knew no language but Kurdish, and a bad interpreter he was. If the conversation became anything more than "What is this?" or "What is that?" he either paraphrased according to his own ideas or else broke down and giggled nervously. The ladies remained and drank tea with me, and then took their leave, while the faqîr presently appeared going his rounds with his flaming dish of wicks, which he had kindled with a brand taken from the coffee hearth — to use a match would be profanation. I noticed that the shaikh, when lighting his pipe, used a flint and tinder.

Faqir Reshu progressed swiftly, almost pattering along [166] on his bare feet up the rocky paths and paved ways, laying his wicks on accustomed places blackened by centuries of illumination, only pausing now and then to ladle out a little oil. The result of his ministrations is that when the sun has left the gorge small flames spring up like flowers everywhere, extinguished as soon as the wick is consumed, when the charred threads, light and brittle, fall to the ground or are blown away. Perhaps, I thought, the mystics who once dwelt here saw in these flames a symbol of human life, a sixth of an hour of life and then black extinction until the Divine Servitor again pours in the oil of life from His inexhaustible store.

Soon after he had passed, Daya Qoteh and the novice set out on their evening visit to the shrines in the valley. Catching a glimpse of them on their way down, I followed at a discreet distance. When I reached the court before the temple I saw the younger, the novice, praying at the open door of the shrine, gazing towards the dim glimmer of lamps in the darkness within. She prayed with hands extended, palms upwards, then bent herself to the ground and kissed the threshold stone, next, the stones by the door, and then the outer wall in several places. Silent as a wraith she moved round the temple court, putting her lips to a stone here, a corner-block there and sometimes a paving-stone, in a methodical way as if she were simply carrying out the usual routine. I heard a childish voice from the nuns' quarters calling to her that food was ready. It was a small girl who often accompanied Daya Qoteh and was, Mammeh told me, her niece. The novice made no sign that she heard, nor did she hurry. Above, in the dusk, I saw the aged nun on the grass-grown roof moving to supper, bowed and slow of gait, and I wondered if the abbess's pretty little niece were destined to this life of devotion, and if so, whether she would end like the Nornlike old creature above us. [167] Daya Qoteh certainly would not, I thought. She came here a widow, her life behind her, and is, moreover, far too intelligent ever to become the husk which is all that if left of her aged sister. After the storms of lay life she is in peace here, and her smile is that of one who has found harbour and happiness.

Hajji, the Yazidi boy, came to me soon after with a distressed look in his brown eyes. Why did I not eat? Why had I refused the meat and chicken which the faqîr had sent us? I explained that I had eaten and enjoyed the excellent rice and burghul, the curds, and spring water, but they must not be hurt by my refusal of meat, because I never ate it, not even in my own house.

"Was I fasting?" they asked, for here there is a religious motive for most things.

"No," I said, and tried to explain that I preferred a meatless diet. They were puzzled and, in the end, I think, put it down to some vow. Do not Yazidis fast before swallowing sacred dust?

As I stood in the forecourt that evening, I saw Venus riding in the night sky.

"Laila!" said Jiddan, gazing up.

He looked for Majnun, but we could not discern lesser

stars, for the spring sky was still light.

[168] "Aye, that is the story."

We looked awhile at Laila, serene in the clear sky,

and then I bade him good night, mounted to my lodging

by the rushing water, and was soon asleep.

[169]

Chapter XVIII: A PLACE OF INFINITE PEACE.

"We sought neither Paradise nor its houris, but contemplation for its own sake." -SHAIKH 'ADI BIN MUSAFIR, Kitâb fîhî dhikr an-nafs.

I woke soon after four o'clock, and seeing the sky flushed with rose-pink, slipped into a warm coat, for mountain air at dawn is sharp, and wandered out, stepping softly as I passed the sleepers rolled in their blankets round the blackened logs of the evening before.

The policeman on watch emerged sleepily from his wrappings, but I silenced him in dumb-show, crossed the courtyard and passed through the arched passage-way which led to the temple-court. In this passage-way, his mat spread in one of the recesses, slept the wood-carving shaikh, but he had already risen to perform his devotions.

I did not go forward into the courtyard, but climbed on to a small stone platform behind a tree which grew there before the shrine. As on the previous evening, the temple-door stood open, and in the blackness of the interior shone the steady yellow flame of an olive-oil lamp. Here, as before, stood one of the white ladies, this time Daya Qoteh, praying as the novice had prayed the night before, facing the east and the lamp within which stood right in the path of the rising sun. At this point I remembered that, although a qawwâl had told me that a Yazidi must face the sun at every prayer-time [170] time, the novice when praying at sunset had stood in the same place and facing the same direction as her superior at this moment. whether the lamp symbolized the sun, or whether the sanctity of the shrine took precedence here, I did not discover. At dawn, however, the qiblas were identical, as the temple is orientated like a Christian church which, indeed, it may once have been. As the abbess prayed and bowed herself at the threshold, a yellow tomcat rubbed himself affectionately against her white robes, arching his back and pressing his head against her. Her movements were precisely the same as those of the novice on the previous evening, and the perambulation of the holy place was the same as she kissed the sacred stones, passing from place to place, the tomcat following with dignity, his tail erect.

At this hour of dawn there was absolute silence except for the voices of wild birds, whose burst of song to greet the day was only just heard above the tumble and gush of the hurrying waters. I stood very still, half-hidden by the mulberry-tree, and watched the quiet figure as it moved, unconscious of my presence. Passing from right to left, she kissed blackened stone after blackened stone, the yellow cat pausing by each like her acolyte. Presently the shaikh passed, and seeing me there facing the east, gave me a shy, kind smile. I saw him moving here and there in the forecourt as I returned, kissing the sacred stones in the grey light, for the yellow light which flooded the upper heights had not yet reached us. On the rocks above the guest-room when I had regained it, I saw Faqir Reshu's little boy Suleyman, a child of eight, walking uphill higher up, entirely alone, and pressing his lips to a sacred rock in the same rapt way as his elders.

All this silent, spontaneous prayer, this unceasing individual reverence of holy places, I cannot help finding more impressive than the mass-prayer of organized crowds gathered under roofs to pray or sing from books, [171] or sermons delivered to half-bored congregations comfortably settled in pews. When I had dressed and walked up the valley I heard the birds pouring out their morning song in one long continuous gladness, and was well-satisfied that I had come to stay at this place at a time when there was no public pilgrimage or feast. The faqîr's wife, who likes gaiety and movement, was eloquent when she described the great autumn Feast of Assembly, when thousands crowd into the valley, the stone-huts are full of pilgrims, male and female, the forecourt full of pedlars and turned for the time being into the bazaar of a temporary town. She described for me the gaiety that prevails in the courtyards where the debka is danced with linked arms round and round over the grey paving-stones, the Yazidi mîr and his sons watching from the platform where the policemen this morning were still sleeping.

The feast, too, I should like of course to see, but I am glad that I came to stay when the shrine was in its normal state of seclusion. I am glad, too, that I rose early and saw the shrine at its holiest moment of first dawn. For it was then that I became convinced that some Yazidis, inarticulate and vague as they are about their own dogmas and beliefs, possess to a rare degree a faculty, as sensitive as the antennae of an insect, which makes them conscious of things outside the material. They have the instinct to be still and worship, which is the very essence of religion. And of all holy places I have ever visited, during sixty years of life in West and East, this valley of Shaikh 'Adi, the Mecca of one of the most sorely persecuted and misrepresented people in the world, seems to me the loveliest and holiest. Here one may find the spirit of the Holy Grail, or perhaps rather of the glad piety of the Saint of Assisi. Something lingers here unpolluted, eternal and beautiful: something as quiet as the soul and as clear-eyed as the spirit.

As I sat on the terrace eating breakfast, I saw [172] Daya Qoteh and the novice returning down the rocky terraces in the bright sunlight with bunches of wild flowers in their hands. Later, I went to visit them, bearing a gift of three red-cheeked Australian apples, They did not receive me in their house, but set cushions for me against the temple-wall, just by the black snake, and sitting beside me on the paving-stones rolled themselves cigarettes, for they think it no sin to smoke. I had many questions to ask, but, as usual, Jiddan's bad interpretership spoilt mutual effort. Our good policeman, when I addressed a question to them, would answer it himself out of his own ignorance, in spite of my "Ask them," or "Tell them." Their courtesy and goodwill, however, helped our stumbling efforts. Jiddan again pressed me to enter the temple, and when I gave the same answer as before, I added, "But you go in, Jiddan!" as it was evident that he wished to do so."

"But, khatûn," he replied disconsolately, "the faqîr will not let me go in again without more karâma" — in other words, another fee.

I pushed him over a hundred fils and in he went after the usual ritual of kissing the threshold and stones. Mammeh and her baby joined us, and as we sat there quietly, an elderly Kurd appeared in the courtyard, his pipe in his hand. Daya Qoteh ordered him, with quiet authority, to remove his shoes before he approached nearer. He obeyed and then seated himself near the temple-door after kissing the sacred stones. Then he told Daya Qoteh. something in an earnest voice and she replied at some length. I inquired of Mammeh the meaning of the conversation. It appeared that the man, who was a Moslem, was in the habit of coming to the shrine of Shaikh 'Adi for some of the miraculous dust which he put upon a leg in which he had hâwa (here, rheumatic pains). After every application, it seems, he felt relief. But now he sought fresh advice about hâwa in his stomach (i.e. stomach-ache). Should [173] he drink tea? Would this or that food or drink harm him? Daya Qoteh told him that he should eat lightly, and that when he drank tea it should be weak and not too sweet, and then, if he rubbed his stomach with Shaikh 'Adi earth and water, "by the power of Allah" he would get well.

At the return of Jiddan, we again tried to converse with the added help of the boy Hajji and Mammeh. I asked about water drunk sacramentally, and Daya Qoteh replied that at the times of the year when the qawwâls go their rounds with the sanjak, that is, the sacred peacock image, they took with them a certain bowl from Shaikh 'Adi and gave the faithful water to drink from the bowl. This seemed to hint at a sacramental ceremony, but, realizing that without Kurdish or a competent interpreter I could do little, I rose and said I was going up the mountain.

"We will go with you," said Daya Qoteh, rising with me.

So a number of us started up the winding uphill pilgrim path which passes some shrines and is well worn though rough. Soon we branched off to a grass-grown track which led steeply upwards, past outcrops of rock, and oaks, and the sacred terebinths. As we mounted higher and higher, valleys and hills unrolled themselves below us in increasingly wider panoramas. When we paused at a rocky turn shaded by an over-hanging tree, we saw a range of snow-mountains rising in their purity behind more lightly covered peaks "Snow," said Daya Qoteh, pointing them out to me. "In Kermanji (Kurdish) bafra." There was a pleasant fiction between us that she was teaching me Kurdish. We perceived below, like the undulating serpent portrayed on Yazidi shrines, the valley track by which 'Aziz and his car had laboured hither. Daya Qoteh pointed out a Kurdish village below, Mugharah; and another nesting on the hills, Atrush.

[174] After the rest, we went upward again, the two white ladies leading the way placidly, never out of breath, for they do nothing else but climb up and down these hills. When the top was reached, we sat and rested again and viewed the mountains, range on range, and the blue valleys between. The summit of the hill — for although it had been steep climbing it was not to be dignified with the name of mountain — was covered with dwarf, wind-blown trees, and a quantity of flowers and herbs. We walked to a large, flat rock enclosed by a rough circular wall of stones, with two entrances, east and west, both so low that to enter one must crawl. Here, hollowed out by human hands, is a round cistern to receive rain-water. Its sides are concave; whether it is of ancient or comparatively modern workmanship it would be difficult to say. In any case, it is sacred, and Daya Qoteh and Daya Rozeh kissed the entrance and threshold stones and the rock round the cistern. It is probably a Shaikh Shems shrine, similar to others on mountain-tops.

Daya Qoteh bent to collect a few herbs, and told me that Yazidi women learn the use of herbs and simples, lore which is transmitted from one generation to another, and that few intelligent women did not know which herbs were purgative, which were febrifuge, or which allayed pain.

Down we scrambled, this time upon the more westerly face of the hill, meeting the pilgrims' way at a higher point, just where a large boulder has been plastered and whitewashed as a sign to pilgrims that from this point they must remove their shoes and go barefoot. At intervals on our crab-like progress from ledge to ledge, we saw below us the flat, grass-grown temple roof surmounted by its three white cones, and the spires of other shrines rising from the leafy bottom, all miniature in the distance.

Hajji showed me a spot from which a Kurdish sharp-shooter , [175] last spring, aimed at the mîr as he was sitting on a roof below. The would-be murderer missed his heart, but wounded the prince in the arm. It seemed an impossibly long shot, for figures seen from here looked the size of flies, so that the Kurd, if Kurd he was, must have been a brilliant marksman. I had heard, however, that the assailant had not been of another faith, but a Yazidi belonging to a faction which resented the mîr's monopoly of the money acquired by the tours of the sacred peacock. It is said that few mîrs die in their beds.

* * * * *

Back in the guest-room I went down to fill a glass from the water which swept past below, while a bystander said " `Awâ.fi"! an ejaculation which should always be made when another drinks to convey the wish that his draught may be healthful. The water is cool and delicious.

I was resting and reading when the door opened and in came the two white ladies bearing copper dishes silvered over and filled with walnuts, almonds, and dried figs. Seeing that I had nothing wherewith to break the walnut-shells, the abbess went outside and returning with a stone, broke one against the ground. I begged them to stay and they seated themselves on the stone floor — cooler, they explained, than the rug — and fingered and twirled their white threads with delicate fingers. I took Daya Qoteh's bundle of white wool from her and tried to imitate their movements, but the thread broke and the spindle did not revolve smoothly as it did for her, so she resumed her work, laughing.

Our conversation was halting and difficult, still, with Jiddan's help and our mutual goodwill we came near understanding each other. I took a photograph of them as they span — alas, in absent-mindedness later I spoilt [176] it by taking another on it! I shall never be able to send them the copy I promised, "so that we can see what we look like", had said innocently these mirrorless white ladies.

Understanding was established between us in spite of words, and when they questioned me about my sons and heard that they were soldiers and my daughter far away was engaged in war work, they showed me their sympathy, and said they would pray for their safety, and there was genuine feeling in their eyes and looks. If I have no photograph of these gracious ladies, so still, so soft of voice and so spotless of dress, I shall always have a picture of them in my heart.

I asked them, through Jiddan, if they had adopted their life by their own wish or because their families had wished it.

"By my own wish," answered Daya Qoteh, smiling tranquilly as she span, but the novice remained silent.

When they rose to go, probably for the midday prayer, I lunched

off curds, bread, cheese, and an apple, an excellent meal. The

light was favourable for Pir Hajjali's shrine, and when I had taken

the photograph to my satisfaction, I wandered uphill with a book to

find the right spot for a siesta, for the guest-room, into which

the sun poured all day, was hot at noon and after. I settled myself

in the shade of a tree, with a rock and my coat for pillow. All

round me grew scarlet ranunculus, purple vetch, wild parsley,

buttercups, iris, spurge, and a quantity of minute flowers which

to me were nameless. As I lay there indolently, I could see the

spire of Shaikh Shems white against green on the next hill, its

golden balls blinking in the sun. The voice of the water was far

enough to make a mere accompaniment of rushing sound, a continuous

murmurous whisper against which I heard blackbirds and heaven knows

what other birds, for their voices mingled in spring symphony with

the hum of the bees.

[177]

The "blunt-faced bees ", as Theocritus called them, were very busy

on the perfumed ledge, their buzz muffled at moments as they crept

inside the bell of a flower. A pleasant place. I drowsed and slept.

[178]

Chapter XIX: CONVERSATIONS WITH MY HOSTS.

"Be sure that those thou look'st on are neither evil, nor the children of evil men." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XXII.

On the previous evening I had sat for a while with the men by the leaping fire on the platform beneath, the company consisting of the three police, the shaikh, Hajji, and the Yazidi lad. We had conversed of countries and towns.

"Is Londra in England, or is England in Londra?" asked the shazkh.

"How big is Londra?" asked someone. "As big as Baghdad, or bigger?"

Then about the war. "This war, now, why has peace not been made? Was it not six months, and nothing had been done? Inshallah, inshallah, the war will not reach us here! But, already sugar has become very dear, and as the khatûn knows, we like plenty of sugar in our tea!" (This was always a grievance.)

Then we passed to speaking of stars and comets, and

one of the older men said that before the last war a large

star, father-of-a-tail, had appeared in the sky; very bright

it was and the tail also.

These sessions by the fire were good for talk, and it was here that the faqîr became communicative. He belongs to an hereditary order, the faqirân. A lad born into the caste need not become a faqîr, but adopts the calling voluntarily. There is preliminary instruction and an initiation, after which the young man anxious to enter the brotherhood fasts for three days before he is invested with the khirqa, a rough woollen tunic worn next to the skin: in olden times, said the faqîr, a forty days' fast was required of them. This tunic, which is the sacred badge of the faqîr, is black in colour, round at the neck and stitched with red wool, falls to the hips, being split at the side of the body from the waist down, and is held round the waist by a sacred girdle. It is of equal length all the way round, not shorter behind, as M. Roger Lescot states in his book about the Yazidis. It is woven of pure lambs' wool and dyed by an infusion of the leaves of the zerghûdh and gazwân (terebinth) trees. "The leaves are boiled with the wool and then, by the grace of God, the white becomes black."

During his fast and the initiation, the would-be faqîr remains in the house and no one must approach him. At its end he takes a hot bath and is invested with the khirqa by his "other brother," who also puts upon him the scarlet woven woollen girdle which goes almost twice round the waist, and a sacred thread of twisted red and black wool round his neck. This thread, called the maftûl, may never be removed. The faqî must wear nothing white, nor may he wear anything between his skin and the khirqa. Faqir Reshu said that when he first wore it, the rough wool irritated his skin, but [180] that now he is used to it. From the day that he becomes a faqîr a man must not cut his beard, but the head is shaved, and Faqir Reshu took off his turban (pûshî) and black woollen skull-cap (kullik) to show me his head.

In the olden days, he said, faqîrs were not allowed to slaughter, but nowadays they are permitted to kill a sheep or fowl when necessary. I asked whether there were a prescribed number of threads in the girdle (shutek), but he replied that there were not. The asceticism of the order is not severe. faqîr may not drink alcohol or smoke, but coffee and tea are not forbidden him, nor is his winter clothing the same as his summer, for in winter he wears a warm waistcoat, the sakhma, and a short outer jacket of red frogged with black, the damîri.

The faqîr is regarded as a holy person and has privileges. In his presence there must be no brawling, and if he arrives when a quarrel is in progress, the dispute must stop instantly. Even a khirqa brought in the absence of the faqîr himself and hung on a tree has been known to check a fight. The faqîr has such authority that he may beat a man as much as he likes and no one may retaliate or lift a hand against him, since it is a sin to strike a faqîr. "The sacredness of the khirqa protects him," commented Jiddan. Second in sacredness to the khirqa, which may be removed and washed when necessary, is the maftûl, the sacred thread described above, which must be washed upon the person, as it may never be removed.

On another occasion I asked the faqîr about fasts and fasting. The subject may have come up because of their concern at my meatless diet. I mentioned to him that Lescot says that faqîrs fast ninety-two days in the year.

"That is wrong," replied Faqir Reshu. "We fast three days at the beginning of Kanun Awwal at the [181] Id ar-Rôja" (the sun-feast at the beginning of December). "We do not fast in Ramadan, but we observe the 'Id al-Fitr ('Id al-Dhâhira) and Bairam as feasts and begin the 'Id al-Dhâhira a day earlier than the Moslems, so that it lasts for four days. We call it the 'Id al-Hajjîyah."

I asked about the 'Ida 'Ezi, the Feast of Yazid.

"That," he replied, "and the 'Ida Roji are one and the same, for it follows a day after the three days' fast. As for the 'Ida Sarsaleh, it is the second feast in importance of all the year." (This was the Spring Feast I had just witnessed in Baashika.)

I asked about the Feast of the Dead, mentioned by Lescot, and he told me that it was identical with the Spring Feast.

All were anxious to tell me about the Great Feast, the 'Ida Jema'iya (Feast of Assembly), when the entire Yazidi world travels to Shaikh 'Adi. It seems that the quiet valley becomes then a town, and its peace is turned into carnival. Every roof, every cave, shelters pilgrims, and many camp out or sleep on the hillside wrapped in a quilt. The sides of the valley at night are covered with twinkling lights. Faqir Reshu hopes to reap a harvest then to recoup himself for his expenditure on his year's tenancy. As I have mentioned elsewhere, it is at this feast that the garlanded bull is sacrificed. The Feast of Assembly takes place in September, and must correspond with the Mandaean New Year's Feast.

Talking of feasts and fasts brought us to those of other religions. I confessed that my abstentions had nothing to do with religion.

"The Nestorians," observed the faqîr, "fast much, and their fast is severe. No meat, no egg, no milk, no butter, and no fat may pass their lips, and in spring they fast thus for fifty days."

"And yet," I commented, "most Assyrian priests are fleshy and fat."

[182] "It is their piety," said the faqîr gravely, "that, by the power of God, fattens their bodies."

* * * * *

During the cooler part of the day I went to visit the southern side of the valley, for I had not completed my tour of systematic examination. Jiddan was pleased to show me the shrine of the shaikh to whose family he is hereditarily attached, namely, that of Shaikh Sajaddin. It will be remembered that there is a shrine dedicated to this shaikh between Baashika and Bahzané, and that Sitt Gulé claims descent from him and from the Angel Gabriel who incarnated to found the family. His mazâr here at Shaikh 'Adi was without a spire, but the treble arch of the doorway was decorated by chevron ornament which gave it a Norman appearance. Dust from this shrine is used to get rid of pests. If cultivation is attacked by locusts, a little is sprinkled on the fields and the insects depart. If rats are a nuisance in storehouse or granary, some of the dust scattered about the place makes them decamp immediately. So say Hajji and Jiddan.

The Yazidi lad who accompanied us showed me warts on his hands and feet. Had I no ointment with me that would cure them? They told me that warts are caused by contact of a person's foot with the urine of a frog, "and wallah, here, where we go barefoot and there are frogs everywhere in the grass, it is an easy matter to come by them."

The next shrine we visited was that of Shaikh Muhammad. The door was a trefoil-headed arch, but otherwise there was nothing worthy of comment about this mazâr. Just above it, the shrine of Pir Hasil Mama (or Mameh?) is decorated with a comb, a gopâl enclosing a star-like figure, and other conventional designs.

| Decorative designs at Pir Hasil Mama. | |

the comb |

the Gopâl |

Close to it on the hillside is a terebinth of great [183] age, with an enormously thick trunk. The next mazâr is that of Shaikh Mand, a more pretentious building, in bad repair. Curiously enough, no snake is represented on its walls, although it is dedicated to the shaikh whose descendants are reputed to have power over serpents. Dust from this shrine, according to Hajji, is good for illness of all kinds, but is not used especially for curing snake-bite.

It grows dark swiftly in the valley, and we stood back to let the faqîr hurry past us with his vessel of oil and flaming wicks. The vessel, I learnt, was called a chirra and the ladle for the sacred oil a kavchak. I closed my notebook and returned.

Presently Daya Qoteh appeared on my terrace, accompanied by the faqîr's sun-browned wife Mammeh, and her black-eyed baby. Mammeh, who tall{ed the Arabic of Bahzané, acted as interpreter. Daya Qoteh had come to take me to task for eating my own food instead of that prepared in their quarters. Why do I not share their food every time they eat?

"But indeed I do both eat and enjoy your food," I protested, and told them how much I had relished the leban they had sent for my luncheon.

They were dissatisfied. "You eat too little. You eat," said Mammeh, measuring her little finger, "so much and we want you to eat so much," and she extended both arms, laughing. "Tonight," she said, "we have made for you a special dolma with no meat in it, so that you can eat it without sin."

[184] I explained again that the only reason I did not eat meat was because, being an old woman, I found it suited my health.

"But you are not so old," they replied, wondering.

"Sixty!" I answered, and showed my hands six times to Daya Qoteh.

"And I," she countered in Kurdish, and I understood her, "am forty-eight. Forty-" she held up her hands too, "and eight!"

"Hashta," I repeated. "That is 'eight'."

"Ha!" said she, delighted, "then you begin to know Kermanji!"

I answered that when I was young I had learnt in my country the language of the gypsies, and that they too said hashta for eight, at which both women wondered.

Daya Qoteh said that I must return here in the summer, for then it was cool and green and the water remained cold as ice. "It is the peculiar property of our water," she explained, "that in winter it is warm and in summer icy-cold."

Again she asked me to tell her about my sons who are soldiers. Although she had not heard of Hitler, the word "soldiers" has an ugly; sound to Yazidis, who have had such savage treatment for resisting military service. Then they summoned me to come with them to the courtyard by the faqîr's house, and there I took my seat on gaily-coloured blankets while Daya Qoteh left with the novice for her evening round of the holy places.