THE MANDAEANS OF ‘IRAQ AND IRAN

FOLK-TALES OF ‘IRAQ

Etc.

[Frontispiece: The holy valley of Shaikh ‘Adi.]

| Avesta -- Zoroastrian Archives | Contents | Prev | peacock | Next | Glossary |

This electronic edition copyright © 2004, J.H. Peterson. If you find texts in this archive useful, please do not copy except for private study ("fair use").

The Yezidis have many customs and beliefs in common with Zoroastrianism, and this text has many observations of interest to students of the latter.

I have been trying to purchase a copy of this book for some time, but have always been outbid by extravagant amounts. Bidding was always vigorous, so I figured there was a fair amount of interest in this text. Therefore, I decided to create this HTML edition.

For an excellent recent book on Yezidism, see Philip Kreyenbroek, Yezidism - Its Background, Observances and Textual Tradition (Mellen, 1995)

Note: All of the page numbers have anchor tags, so can be referenced individually, for example, http://www.avesta.org/yezidi/peacock.htm#p30. Likewise, the chapters can be referenced, for example, http://www.avesta.org/yezidi/peacock.htm#chap3. Obvious typos have been silently corrected.

Please let me know if you find any typos, or have suggestions for improving this e-text or web site. Thanks. -JHP, July 2004.

Author: Drower, E. S. (Ethel Stefana), Lady, b. 1879 Title: Peacock angel; being some account of votaries of a secret cult and their sanctuaries Published: London, J. Murray [1941] Description: ix, 214 p. front., illus., plates, ports. 22 cm. Availability: TC Wilson Library 297 D839 Regular Loan Subject LC: Yezidis. Material Type: bks

|

PEACOCK ANGEL Being some Account of Votaries of a Secret Cult and their Sanctuaries E. S. DROWER * LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. |

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| PRELUDE | 1 | |

| I | BAASHIKA | 10 |

| II | A YAZIDI WEDDING | 18 |

| III | SNAKES AND SHRINES | 24 |

| IV | BIRTH | 30 |

| V | BAHZANÉ AND SHAIKH UBEKR | 40 |

| VI | SITT GULÉ | 48 |

| VII | THE MONASTERY ON THE ROCK | 61 |

| VIII | "SAIREY GAMP" AGAIN | 70 |

| IX | A JACOBITE SERVICE | 79 |

| X | LEGEND AND DOCTRINE | 87 |

| XI | THE EVE OF THE FEAST | 97 |

| XII | THE FEAST: THE FIRST DAY | 102 |

| XIII | THE FEAST: THE SECOND DAY | 110 |

| XIV | THE FEAST: THE THIRD DAY | 124 |

| XV | PILGRIMS' PROGRESS | 136 |

| XVI | SHAIKH 'ADI: THE TEMPLE PRECINCTS | 151 |

| XVII | THE SHRINES OF SHAIKH 'ADI | 159 |

| XVIII | A PLACE OF INFINITE PEACE | 169 |

| XIX | CONVERSATIONS WITH MY HOSTS | 178 |

| XX | STORM IN THE VALLEY | 187 |

| XXI | WITHIN THE TEMPLE | 194 |

| ENVOY | 203 | |

| APPENDIX A: MARRIAGE CUSTOMS | 207 | |

| APPENDIX B: BIRTH | 208 | |

| GLOSSARY | 210 | |

| INDEX | 211 |

Sincere thanks are offered to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Baghdad, to the Mutesarrif of Mosul, to His Highness the Mir of the Yazidis, and to Captain Corry, of the ‘Iraq Police. Mr. Evan Guest was kind enough to supply the botanical names of the plants mentioned in this book.

I must also add my very grateful thanks to my

daughter, Miss M. S. Drower, for correcting the proofs;

as I am out of England, it was impossible for me to do

this myself.

Note.— The quotations at the heads of the chapters are, with

one exception, from Andrew Lang's Translation of Theocritus, Bion

and Moschus. (Macmillan, 1889).

[1]

PRELUDE |

NOTES: |

"When the hoary deep is roaring, and the sea is broken up with foam, and the waves rage high, then lift I mine eyes unto the earth and trees...." -MOSCHUS, Idyll V. I had invited the Yazidi princess to lunch with me in our house by the Tigris in Baghdad. She rang up from her hotel to reply. I said, "Who is it?" A voice replied, "Wansa; it is Wansa speaking." "Did you get my note, Mira Wansa?" "Yes, thank you very much. Madame, I will come. Madame, you are very gentle." She had learnt some English and French in Beirut, so what she meant was "it is very nice of you to ask me." This girl had been expelled from Syria. When she ran away from her husband, the ruling prince of the Yazidis, she crossed the frontier by way of the Jebel Sinjar, her real home, to shelter with co-religionists in Syria, for assassination would have been her certain portion had she stayed. At twenty-four life is sweet, although the marriage arranged by her father, Ismail Beg, had been a tragic mistake, and although she had lost her only daughter Laila as well. She spoke of her with tears in her eyes: "Madame, I loved her!" Malaria, the curse of the Kurdish foothills, claimed this little victim and so snapped the only remaining link between the young princess and her husband. The refugee was without a passport in wartime and the French authorities were suspicious. She was placed in an hotel under military supervision, but it was not [2] considered advisable to allow this charming young woman, whose name was suggestively "Amusement” (Wansa), to remain in the country. Considering the times, this was natural. Coming as she did from a country where nationalism takes the form of an active interest in neighbouring politics, she became the object of doubts. Finally, as “a menace to public security” "Wansa, Princesse des Yezidis" was sent back over the frontier again and placed herself under the protection of the ‘Iraqi Government. She established herself in an hotel in Baghdad, with her mother and brother, and was far from friendless, since several schoolfellows in Beirut, ‘Iraqi of origin, lived in that city. Whenever she goes out, however, she is guarded, for assassination lurks round the corner for her even in Baghdad, and to return to her own people would be suicide. When she came to see me, the policeman detailed to accompany her waited by the house till she came out. Yet she yearns for her hills, like that Median princess for whom the Babylonian king, her husband, built an artificial mountain, called misleadingly the Hanging Gardens. She talked to me of her home in the Sinjar, and answered all my questions about the habits and customs of her people with an appreciation of the points which showed cultivated intelligence. She is the first Yazidi woman to be educated. Her father, Ismail, of the princely family, broke with tradition by sending her to school, and the failure of her subsequent marriage with the ruling prince, a man older than herself and himself unschooled, has led the wiseacres to shake their heads and say, "There, we said that no good would come of teaching a woman to read." When I first visited the Yazidis in the north eighteen years ago, practically no Yazidi boy attended school, and none but a few of the religious shaikhs could read. Education was forbidden. Now it is different. At the [3] village of Baashika, where I spent part of April this year, many Yazidi boys attend the local Government school. A few have passed into the secondary schools, and before long there will be a supply of Yazidi school-masters to teach Yazidi children: indeed, there is one already in the Jebel Sinjar. The parents, mostly farmers, are not yet enthusiastic. They fear, and perhaps with reason, that if their sons go to school they will find agricultural work demeaning and will hanker, as often happens, to become clerks and petty Government officials. To remove this fear should be the task of the schools, and I hope that the Yazidi teachers, themselves not town-bred, will be able to implant in their pupils a true pride in work on the land which bred them, as well as interest in anything which may improve traditional methods of tillage. To exchange their natural heritage for the office-stool and coffee-house, for the empty life of the effendi, would be the sorriest of bargains. Too often, enthusiastic schoolmasters see in successful examination results and office employment the goal for every scholar, no matter what his origin, with the result that the peasant lad leaves his village and becomes a drug in the towns. This is to question the fairy gold which the Little People place at the cottage door, for which the punishment is that the gold turns to black coal. As for the girls, their time will come: meanwhile, I wonder how much these peasant women lose by not being able to write their names or read the cinema captions, accomplishments which are, too often, the only result of education in a country where a woman rarely opens or reads a book after leaving school unless she has taken up a profession. No, these Yazidi women cannot read. They cannot read the fashion papers, or news columns, or even the advertisements of patent medicines. But they grind the grain which their men have [4] harvested, they work in the fields, they bake, they cook, they milk, they make butter, they weave, dye, bleach, sew and wash clothes. All day and every day in Yazidi villages one hears the clop-clop of wooden clubs as they beat the family washing at the springs, great tablets of home-made olive-oil, soap beside them on the stones, and garments and cloths spread on the hot rocks to dry. The washing-pools are the women's clubs: here they gossip, and here reputations are made and lost. All this is in addition to the work of bearing and suckling children, which not a woman shirks or evades. I heard many charms for curing barrenness, but never of a contraceptive or of any spell for the prevention of child-birth.

I had intended to revisit the Yazidis for some years

past, and not as a quickly passing traveller, but to stay

long enough with them to know something of their

daily lives and doings. In the spring of 1939 I was

upon the point of starting when a rumour, started in

the bazaars after the sudden accidental death of the

young King Ghazi, led to trouble in the north. Anti-British

feeling had long been prevalent in the schools,

and in Mosul schoolboys led a rush to the British Consulate.

But a short while before, these same schoolboys

had been the Consul's guests, and it was his trust in their

friendliness which led to his coming down unarmed,

and to the brutal attack which killed him. It was not

their fault. They believed that we had treacherously

killed their king, and answered supposed treachery with

treachery. The lie still lingers, for truth is too simple

to be believed by a generation trained to expect intrigue

from every European. It is a disadvantage to Truth

in any Oriental country that she is naked. They expect

her, like every decent woman, to be well covered and

veiled. For this reason, plain statements of fact over

the radio have little chance of being credited. Coffee-house

wiseacres shake their heads. "It is all propaganda,

[5]

Both sides have their propaganda. Both sides

tell lies. It is natural."

As Mosul was my jumping-off place, this unfortunate affair wrecked my plans, and it was not until this spring of 1940, in the lull which preceded the German offensive, that I was able to carry them out. Wansa's visit to Baghdad was opportune, for she most kindly gave me a letter to friends in Baashika, as well as satisfying my curiosity about many things I wished to know. Here I must apologize for this book. It is not a serious contribution to the literature about the sect, although when I went the ostensible reason of my visit was to see how the Yazidi spring festival fitted into the pattern of the other spring festivals of an ancient and conservative land. Being there, however, female inquisitiveness led me into byways, so that those who really do mean to study this interesting people scientifically and thoroughly, may find here scraps and tags of information which may be useful to them. I hope sincerely that some honest and skilled investigator may undertake the task, for I am convinced that most of what has been written hitherto about the Yazidis is surface scratching, often incorrect, based upon hearsay instead of upon prolonged direct investigation. Without a good knowledge of the Kurdish language it would be impossible to gain the confidence of the religious chiefs or to understand chants sung by the qawwâls. In a book I wrote eighteen years ago, I repeated many tales about the Yazidis current amongst their neighbours, and others have taken their material from similar sources, and sometimes borrowed from my chapter. At all these legends, reports and current tales I look now with the utmost caution and suspicion. Years spent in studying another minority and another secret religion have taught me how unreliable hearsay evidence is, and in this book, therefore, I repeat only what [6] I gather from Arabic-speaking Yazidis themselves, or that which I myself witnessed. The Yazidis are spoken of as Devil-Worshippers. Apart from the fact that Shaikh ‘Adi bin Musafir, their principal saint, was recognized in his time as an orthodox Moslem, my personal impressions are contradictory of this. I cannot believe that they worship the Devil or even propitiate the Spirit of Evil. Although the chief of the Seven Angels, who according to their nebulous doctrines are charged with the rule of the universe, is one whom they name Taw'us Melké, the PEACOCK ANGEL, he is a Spirit of Light rather than a Spirit of Darkness. "They say of us wrongly," said a qawwâl to me one evening, "that we worship one who is evil." Indeed, it is possibly the Yazidis themselves, by tabooing all mention of the name Shaitan, or Satan, as a libel upon this angel, who have fostered the idea that the Peacock Angel is identical with the dark fallen angel whom men call the Tempter. In one of the holy books of the Mandaeans the Peacock Angel, called by them Malka Tausa, is portrayed as a spirit concerned with the destinies of this world, a prince of the world of light who, because of a divinely appointed destiny, plunged into the darkness of matter. I talked of this with the head of the qawwâls in Baashika who, honest man, was not very clear himself about the point, for one of the charms of the Yazidis is that they are never positive about theology. It seemed probable to me, after this talk, that the Peacock Angel is, in a manner, a symbol of Man himself, a divine principle of light experiencing an avatar of darkness, which is matter and the material world. The evil comes from man himself, or rather from his errors, stumblings and obstinate turnings down blind alleys upon the steep path of being. In repeated incarnations he sheds his earthliness, his evil, or else, if hopelessly linked to the [7] material, he perishes like the dross and illusion that he is. I say that this seems to me a probable conception, but I have no scrap of evidence that it is the Yazidi theory, no documentary proof, no dictum from the Baba Shaikh, who is the living religious head of the nation. One Yazidi propounded to me the curious theory that the accumulated experiences of various earthly lives was, on the Day of Resurrection, gathered into one over-soul, but that the individuals who had once lived those lives continued as separate entities, but how this was possible he did not explain. However, as I have already intimated, I am not concerned here with Yazidi creeds, but with themselves and the shape of their daily life as I saw it. Whatever may be the vague beliefs of their religious chiefs, their practised religion is a mystical pantheism. The name of God, Khuda, is ever on their lips. God for them is omnipresent, but especially reverenced in the sun, the planets, the pure mountain spring, the green and living tree, and even in cavern and sacred Bethel stone some of the mystery and miracle of the divine lie hidden.

As for propitiation of evil, I can say sincerely that

I found less amongst them than their neighbours.

Moslems and Christians wear three amulets to the

Yazidi one, and though a Yazidi is not averse to wearing

a charm against the Evil Eye, many so-called devil-worshipping

children go without, though few Moslem

or Christian mothers would dare to take their babies

abroad without sewing their clothes over with blue

buttons, cowries, and scraps of Holy writ, either Qur'an

or Bible.

| |

|

A third impression was of their cleanliness. In the

village of Baashika there was no litter, no filth, no mess

of discarded cans or scattered bottles. To be honest,

I saw a few rusty tins, but these had been carefully

[8]

collected, filled with water, and taken to a shrine,

there to be left as offerings. Petroleum-tins are utilized

to store precious home-pressed olive-oil, so that pitchers

and jars are still employed for water-carrying. Paper

is rarely used. What one buys in the bazaar is taken

home in a kerchief or in a corner of the robe. There

is no faint and revolting stench of human filth such as

there is in most Arab villages in central and southern

‘Iraq, or on the outskirts of the larger towns, where

any ditch or wall serves for a latrine. As a newspaper

is a rarity, one sees no untidy mess of soiled paper.

What they do with their dead animals I do not know,

but I neither saw, nor smelt, a decaying corpse, whereas

even in such a modern town as Baghdad, owing to the

laziness of municipal cleaners who dump dead animals

behind the city to save themselves the trouble of the

incinerator, any walk outside the city area may mean

breathing polluted air. I complimented the mayor of

the village, and he replied simply, "They are clean

people."1 Nevertheless, to the authorities belongs

the credit of tapping the pure spring water as it issues

from the mountain at Ras al-‘Ain and bringing it by

pipe to the centre of the village so that women can

fill their water-pots with good water.

|

1. Layard comments upon Yazidi cleanliness. |

|

At Shaikh ‘Adi I realized what a danger people like

myself can be to such a place when I saw the result of

my giving a page of pictures from an illustrated paper

to the children of the guardian of the shrines. Quickly

tiring of looking at the images, they tore it up and the

untidy fragments were borne by the wind about the

flower-grown courts of the sanctuary.

To return to this book. It would be tedious to recount all the conversations which led to such information as is set down here about marriage and birth and such events. I have therefore woven them, I fear in a somewhat haphazard way, into the narrative of the [9] whole. The book is, therefore, merely a personal impression of day-by-day happenings and friendships. To me this stay of a spring month with the Yazidis was a very lovely experience, and if I fail in transmitting its flavour and quality, it is that I am incompetent. To have escaped in the midst of a European war into places of absolute peace and beauty is an experience which one would gladly share with others.

An old friend of mine in this city of Baghdad, echoing

unconsciously an ancient belief, once told me that if

ear and spirit can be cleared of the din of this world,

one can hear at rare and high moments the separate

notes that the worlds give forth, the sun, the earth,

the moon and the stars, as they move and vibrate according

to the law of their being. The whole blends, he

said, into perfect harmony, into an exquisite chant of

joy. Whatever this music may be, and whatever its purpose

or purposelessness, I fancied that, for a moment or two,

during these weeks of escape, I caught a fleeting bar, a

faint echo of lovely and eternal harmonies, far removed

from the clash and fret of men.

Chapter I. BAASHIKA."Not of wars, not of tears, but of Pan would he chant, and of the neatherds he sweetly sang...." -THEOCRITUS. I was to stay with friends in Mosul, and it was my host, Captain C., who had taken infinite trouble in arranging for me, with the permission of the authorities, lodging in the Yazidi village that I had chosen as my headquarters. The road thither is impassable in wet weather, and I felt apprehensive when Captain C. showed me pock-marks more than an inch deep in his flower-beds, and plants battered to the ground by hail which had fallen the day before. I was still more anxious when the sky darkened as if Sindbad's roc were approaching. Sure enough, rain followed, heavy and sharp, but the C.s comforted me. A sun next morning and a good wind would dry the road at this time of the year, they assured me.

And so it was. I woke to a blue, rain-washed day.

Whilst I paid calls upon the Governor and Mayor,

the roads were drying in the bright sun and fresh

wind, so that all was well for our start. A kindly

thought had led the local officials to allot me a Yazidi

policeman as guardian and guide, an honest-looking

lad who spoke Kurdish as well as Arabic, and therefore

could act as interpreter when the latter language failed.

As a guardian he was unnecessary, but he proved to be

a pleasant companion. He and his baggage were

stowed into our taxi and off we went.

| |

|

The road to Baashika is only so-called by tradition.

[11]

It is really an unmade track through the cornfields and

it was still extremely soft and muddy. At times the

car waltzed disconcertingly, and here and there the

driver forged through the corn in order to avoid a bog.

At the worst places we got out and walked, and that

was enjoyable, for though our shoes became clogged

with mud as we walked through the corn and bean fields,

the larks were singing rapturously, the hills and snow

mountains grew nearer mile by mile, and wild flowers

grew amidst the blades. I was glad to find out that

Jiddan, our policeman, being hill-bred, knew the names

of the flowers, sometimes in Arabic and sometimes in

Kurdish. He never ceased to be amused by my passion

for knowing the names of flowers, trees, and herbs.

What did it matter? and indeed, what does it matter?

However, I liked, for instance, to be able to name the

small and extravagantly sweet yellow clover that grew

everywhere, nôfil,1 and to learn the familiar words by

which field plants and herbs are known to the countryman.

Perhaps in the Garden of Eden, while Adam

was naming the animals, Eve named the flowers.

|

1. One of the trefoils. Mr. Evan Guest suggests Trifolium procumbens. |

|

I had visited Baashika before. It lies at the very

foot of the hills of the Jebel Hamrin range, and the

white-washed cones of Yazidi shrines rise above the

olive-groves with which it is surrounded. We passed

by these groves and then by a very new and imposing

church, not at all unsightly, but, I discovered, not loved

by the Jacobite Christians of the village. "The Pope

built it for the Latins with Italian money," they say,

"whilst we paid for our church ourselves." Perhaps

I should not call them Jacobites, for they prefer to be

called Syrian Orthodox Christians. They have nothing

to do with the Pope and the Pope nothing to do with

them, and they look upon their ancient Oriental communion

as superior to that of the Latins. The Uniate

[12]

churches are monied and subsidized; the communities

of the Non-Uniates are poor but proudly independent.

Of that later. We were immediately concerned with arrival and settling into the tiny house which had been allotted to me. The house was clean, swept, and garnished. Two bedsteads, a table, two benches, and four chairs had been provided for us. It was all that we needed, indeed more, as I had already a camp-bed and such pots, pans, and household gear as were necessary. I had asked A. to come and spend a few days with me if she could, and had warned her that if she came she must bring her own bed and mug and plate. The house consisted of a tiny kitchen, a room on the ground level, a living-room and a small room off it, both two steps up from the grass-grown courtyard. Steps led to the flat roof, half-way up being the usual Oriental latrine, a hole in the floor. A dry basement was assigned to my servant, Mikhail, the little room off the living-room reserved for A. should she come, and Jiddan elected to sleep on the roof. So that we were all comfortable and happy. I had just lunched, unpacked, and gone to salute the mayor of the village who was sitting comfortably on a bench in front of the police-post, when there was an arrival. Captain C., piling thoughtfulness on thoughtfulness, had arrived with a rug, some curtains, and one or two other details which he thought might add to our comfort. He had no time to stay; he just bestowed his benefits and made off again on the muddy road to Mosul. The first thing to do was to get into touch with the Yazidis themselves. So I got out a letter which Mira Wansa had written for me to her friend Rashid the son of Sadiq, and went in search of him. The main village street had a deep ditch running down its centre to carry off winter torrents, but, though this was empty, it was not used as a rubbish dump. Jiddan walked modestly a pace or two behind me, and though we conversed [13] all the way, the dialogue was over my left shoulder. The house of Sadiq stood at the farthest end of Baashika and, as he is a man of some substance, it was one of the larger houses of the place. A stone archway, in the shadow of which were seats, admitted us to a large courtyard full of fruit-trees, down which a clear stream ran in a paved bed. On two sides of this courtyard were living-rooms, those on one side being shaded by a pergola of vines. Outside these an aged lady wearing the Kurdish turban was engaged in some house hold task. She spoke nothing but Kurdish, but Jiddan explained as she came forward hospitably to meet us and place chairs for us in the shade, whilst someone went to find her son. Her husband, Sadiq, she told us, had gone to his estate in the Jebel Sinjar, but hoped to be back for the spring feast. Even as she was speaking Rashid, her son, arrived. He was a young and good-looking man with a face full of energy and intelligence, for whom one immediately conceived liking and respect. I handed him Mira Wansa's letter, which he frankly admitted that he could not read. There is no shame here in admitting illiteracy. Reading and writing are priestly accomplishments, just as amongst the tribes, until recently, such soft and clerkly arts were despised by the shaikhs, each of whom kept a private scribe. Amongst the Yazidis, as already said, school education was until lately forbidden by religion. Rashid, however, is having his own children educated and has a brother who is a schoolmaster in the Jebel Sinjar. He told me laughingly that the learning of his brother was so much esteemed there that his opinion was asked about everything. "He is not only a schoolmaster, but a doctor, a lawyer and a judge, and they even ask him to write charms for them." He busied himself about making tea for me, kindling [14] wood in a brazier and boiling a kettle in the capricious shade of the freshly-leaving vines, then pouring the clear brown tea into waisted Persian glasses, called istikâns. Meanwhile, Jiddan read him the letter, after which I tried to explain to him why I had come. I wanted to see the Spring Festival, and asked his advice as to the better place to be in for the feast-days, Baashika or Shaikh ‘Adi? Shaikh ‘Adi is the Mecca of the Yazidis, the great shrine to which all travel at least once in a lifetime and at every Feast of Assembly if they can. The Feast of Assembly, sometimes called the Great Feast, takes place annually in early autumn, but the Spring Feast, Sarisal or Sarsaleh, falls on the first Wednesday of Nisan in the Eastern calendar, which coincided this year with the middle of the Occidental April. Rashid considered. "Your Presence has been to Shaikh' Adi," he said, "and so knows that at Shaikh ‘Adi there is the shrine and the valley, but no village. They keep the feast there, it is true, but not as we keep it here. This feast is the feast of the people, and here there are plenty of people, and Yazidis and Kurds come in from all the hills and neighbouring villages to see the feast and the tawwâfi. Here it is a much better thing than at Shaikh ‘Adi. People even come from Mosul and Kirkuk to see the dancing." Jiddan corroborated him. "It is well known that the feast at Baashika is better than at any other place." Without committing myself to any decision as yet, I tried to tell him my other purpose, which was, without inquisitiveness, to learn something about his people and his religion. "I feel sure," I said, "that much of what others say about you is false, and I have learnt that only what I see with my own eyes and verify for myself is true!"

Rashid promised to help me. "But as to religion,"

he said, "I cannot assist you, as we laymen know little.

[15]

It may be difficult for you. I will bring you some of

the qawwâls, but—" he broke off, doubtfully and

then added, "No doubt, when you get to Shaikh ‘Adi

the Shawish will tell you much about our religion, for

he talks Arabic as well as Kurdish and lives always at

the shrine."

| |

|

Here I should explain that the Yazidi priesthood is

graded and subdivided. The religious chief, the Pope

of the cult, is the Baba Shaikh, who lives at Shaikhan

(‘Ain Sifni). He is head of all the shaikhs, who constitute

the highest order of priesthood. The shaikhs

are supposedly the lineal descendants of the companions

of the sect founded by Shaikh ‘Adi early in the twelfth

century, although these were so pure, says Yazidi legend,

that they created their sons without the assistance of

women. These miraculously begotten sons, however,

took wives to themselves and founded families. The

shaikhly families are of a racial type markedly different

from the Yazidi laymen, being darker and more Semitic

in appearance. They exercise what are almost feudal

rights over the laymen, each lay family being attached

to a certain shaikhly family. Only the shaikhly class

are instructed in the inner doctrines of the faith, and

until lately only the shaikhs, especially the family of

Shaikh Hasan al-Basri, could read or write. The

shaikhs officiate at marriages, at birth, and at death,

and it is from a shaikhly clan that every layman and

laywoman choose the "other brother" and "other

sister" whom he or she is bound to serve in this world

and the next. Of this more in a later chapter. Moreover,

a shaikh may not marry outside his caste, and

the portion of a daughter who marries outside it is

death. A sub-functionary to the Baba Shaikh is called

the Pesh Imâm.2 Below the shaikhs come the pîrs.

A pîr must also be present at religious ceremonies, and

[16]

acts to some degree as an understudy of the shaikh, as

he may take his place if no shaikh is available. Like

the shaikhs, they are credited with certain magic powers.

The qawwâls constitute the third religious rank. They

are the chanters, as their name signifies, and the chants

which they recite to music on all occasions are not

written down, but words and music learnt in early

youth are transmitted from father to son. They must

be skilled in the use of the daff, a large tambour, and

the shebâb, a wooden pipe. Like shaikhs and pîrs,

qawwâls may not marry outside their caste, and they

do not cut the hair or beard. Most of the qawwâls live

at Baashika or Bahzané, its sister-village, and it is they

who travel near and far with the images of the sacred peacock,

in order to visit which the faithful pay money,

so that they are usually men of the world, since their

tours until lately included Russia, Turkey, Iran, and

Syria. The next hereditary order is the faqîrs, but of

them I will speak when I come to my stay at Shaikh ‘Adi.

There are non-hereditary orders as well, the

kocheks, ascetics who wear nothing but white, dedicate

themselves to the service of the shrines, and are credited

with seeing visions and prophetic gifts, and lastly,

the nuns, the faqriyât, who are vowed to celibacy,

wear white, and spend their lives in the service of the

shrines at Shaikh ‘Adi. As to the Shawish, of whom

Rashid spoke, he has his permanent dwelling there,

but, not having seen or talked with him personally,

I am not clear as to his functions and powers.

|

2. Lescot states erroneously that the Baba Shaikh and Pesh Imâm are one and the same person. |

|

Immediately helpful, Rashid at once sent in search

of a qawwâl who lived in the village; meanwhile,

I took up the tale of my wants. I hoped, I said, to

learn something of Yazidi ways, how women lived and

managed their households, brought up their children,

and lived their daily life. I should like, I said, to

talk to the village midwife and to go to a wedding,

should there be one.

[17] The midwife was easy, Rashid replied; he would send her to me, but perhaps I had heard that the coming month of Nisan was forbidden for marriage? The pity was that there had been two weddings in the village only last week.

"We cannot order such things," I said, laughing;

"moreover, I have assisted once at a Yazidi wedding

when I stayed with your mîr at Ba'idri."

Chapter II. A YAZIDI WEDDING"In Sparta once, to the house of fair-haired Menelaus, came maidens with the blooming hyacinth in their hair. . . ." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XVIII. I shall not easily forget what I saw when I stumbled upon a Yazidi wedding one October, in the village of Ba'idri, where we were staying the night with Wansa's husband, the mîr, at his qasr or castle on the hill girt about with sacred trees. On the slopes men and women were dancing to the pipe and drum, all in the gayest of colours, the huge silver buckles and silver headdresses of the women flashing in the sun as they swayed and stepped to the music. It was the round mountain dance, the debka, which I was presently to see in its original religious form at the Yazidi spring feast. Within an upper room of her father-in-law's house sat the twelve-year-old bride in semi-darkness, for a veil had been drawn across the half of the room where she sat on her-bridal bed, silent as custom insists. The sun must not shine upon her for a week, they said. It was Mira Wansa herself who told me most of what I set down here, prompted by questions which I will leave out. It is the parents, she said, who arrange a marriage, but they often know already the wish of the son or daughter concerned. The parents of the young man approach those of his prospective bride. Her father asks the girl if she accepts, and her silence gives consent. Should the match be abhorrent to her, she is permitted to speak out and to refuse. The families [19] being agreed, the bridegroom's father, accompanied by a shaikh and a pîr, goes to the, girl's father to discuss the dowry (Kurdish, nekht). When this is settled — a sum of forty dinars is the average sum for a family of moderate means — the shaikh writes the agreement on paper, affixes his seal to the document and then reads prayers invoking the blessing of the Peacock Angel and other angels upon the union. The clan of Shaikh Hasan is considered especially fortunate at a marriage and a shaikh of this sinsila (clan) should be present at every wedding. The shaikh presents the bride with some earth from the shrine of Shaikh ‘Adi, and she, in return, gives money to him and to the pîr, or, it may be, gifts in kind such as a sheep and goat. The value of the gifts depends upon the means of the family. The period between this ceremony and the going of the bride to her future home varies: it may be a few days or some years. Two days before the consummation of the marriage the bride takes a hot bath, and from this moment she must wear nothing but white. The next day, the hands of the bride and of all her friends are dyed with henna. A large dish of henna is prepared and taken round to the houses of neighbours and friends, sometimes to all the village. Women and girls help themselves to the henna and put money into the dish as a wedding gift. If the bridegroom is of another village, the day before the wedding all the girls and youths of that village travel to the bride's village, the girls riding three or four on a mule, while the boys and young men mounted on horses gallop about the procession singing and shooting into the air. The young men sleep as guests in various houses, the girls stay that night with the bride. At about four o'clock in the morning the girls and women rise, go to the bride, and dress her in her bridal clothes and ornaments, while she remains [20] entirely silent. If she can weep, and, the mother can weep, it is of good augury. No matter how pleased both may feel inwardly at the marriage, weeping is not only a sign of modesty on the part of the bride, but also helps to keep away the Evil Eye. The handsomest part of a Yazidi girl's gala dress is the huge embossed gold or silver buckle which fastens her belt, often wider than the girth of her slender waist. Only one girl is allowed to clasp this heirloom, and that is the bride's "other sister". I should explain what this "other sister" and "other brother" means. A lay girl and boy choose their "other brother" and "other sister" for themselves. The choice may not be made until after puberty and is sometimes left until late in life. The person chosen must be of the shaikhly class, either of the shaikhly family to which the young man or woman is hereditarily attached or of another, it does not matter which. The choice must be made and acknowledged at Shaikh ‘Adi and usually takes place at the great September feast at the time of the universal pilgrimage to the shrine. The ceremony is simple. The man (or woman) of the shaikhly caste chosen fills his (or her) right palm with water from the sacred spring of the shrine and the young commoner drinks it from the hand of the chosen liege lord or lady. Henceforth there is a close tie between the two. The "other brother" has duties to perform at marriage, birth, and death and must protect and help his brother in every way. The commoner on his part must make his "other brother" a present yearly and serve and help him always, "not only in this world, but in the next, even in hell". Yazidis look upon this curious dual duty as prolonged into other lives: the link between the two has existed before this life and they will come together in future lives. A girl must have an "other sister", but she may also choose an "other brother" if she wishes to do so, and so also with a boy. [21] This is not usual, but may happen, and implies a yearly offering and acceptance of gifts. The relationship is entirely platonic, though usually accompanied by admiration, and is a free choice, for to marry a commoner, however beautiful, is forbidden to a member of a shaikhly clan. The final touch to the bride's robing is her veil, which is red, and when all is ready the veiled girl takes leave of her weeping mother and is set on a horse. A man of her own village, but not a shaikh or a pîr, holds the bridle and leads the horse as the procession forms and sets out. The young men of the bridegroom's village are careful to provide themselves with small coins before they start, for it is the duty of the small boys of the bride's village to pelt the young men in the procession with all the small stones and garbage they can find, while the young men distract these attentions by throwing money. All this is carried out, said Wansa, with much gaiety and jesting. Before the last house of the village, the bridegroom's party presents some money to the headman (mukhtâr). When the procession has reached the bridegroom's village and house the mother-in-law, standing on the roof of the entrance, showers sugar, sweets, and flowers over the bride as she arrives on her horse. The bride's "other sister" helps her to dismount. Then the bridegroom's mother, coming down, hands the bride a jar filled with sugar and sweetmeats. Before the new daughter-in-law can enter, she must hurl this against the threshold-stone, so that it breaks, and the sweets are scattered. For these everyone scrambles as they bear good fortune. The bride steps into her future home over the broken fragments and also over the blood of a sheep whose throat they cut just by her feet. Before she goes into the bridal chamber there is a mock battle between young men of the bride's party and those of the bridegroom for the possession of the [22] latter's headgear. When one or the other succeeds, the bride puts money into the bridegroom's cap and gives it to the youth who succeeded in capturing it.

Throughout all these merrymakings the bride remains

silent as an image, and is veiled in red. When she has

entered the bridal chamber, the shaikh and pîr tie a

curtain (sitâ) across the room. For seven days she

and the marriage bed must remain behind this curtain

or veil, and when she is forced to emerge in order to

obey a call of nature, she must be careful not to pass

over any water.

| |

|

On the day that the bride comes to the house the

bridegroom himself stays away, remaining elsewhere

with his "other brother". Should the day of arrival

be a Tuesday, no consummation of the marriage can

take place that night. The bridegroom must spend

that night and the next day at another house in

the "other brother's" company, and join the bride

on the Wednesday night at midnight. This is because

Wednesday is the Yazidi holy-day and Tuesday night, as

we should call it, is for them "the night of Wednesday".

| |

|

When the young husband enters the bridal chamber

at midnight, his "other brother" and two of his friends

wait outside the door of the room. The bridegroom is

allowed an hour to consummate the marriage.3 After

this has been announced, the young men and bridegroom

eat of some light food which the bride must

be mindful to take with her into the bridal chamber,

and then all go to sleep.

|

3. See Appendix A. |

|

"At the end of the seven days the bride may leave

her room. She takes a bath, and women of the bridegroom's

village prepare a large dish of dates, together

with seven kinds of grain — wheat, lentils, oats, beans

(bajilla), fûl (another kind of bean), and round pease

(verra). These they boil together on the fire without

butter or fat or any other ingredient. Then, carrying

[23]

this porridge, they go out in gay clothing to the meadows,

taking the bride with them till they reach a stream

or running water. The bride must put seven handfuls

of it into the water, cross the stream, and eat it with

her friends. When the oleander is out," continued

Wansa, happy memories in her eyes, "this is a pretty

sight. We think that oleander is a powerful amulet

against the Evil Eye, and make necklaces of it. So the

women and girls who accompany the bride, sometimes

fifty or more, put the pink blossoms in their turbans."

During the imprisonment of the bride her friends feast and make merry. From dawn till ten of the morning flute and drum sound and men and women dance the debka. From ten till the early afternoon they rest and eat. Then dancing begins again and goes on till midnight. "This is the time," said Wansa, "that young lovers prefer, for they may find themselves dancing near together and can hold hands in the circle."

Certain inauspicious women are forbidden to go near

a bride: a woman during her period, a woman from

a house of death, and a woman who has borne a child

until her forty days of uncleanness are ended and she

has taken the bath which makes her no longer dangerous.

Chapter III. SNAKES AND SHRINES"Then these twain crawled forth, writhing their ravenous bellies along the ground and still from their eyes a baleful fire was shining as they came, and they spat out their deadly venom." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XXIV. | |

|

Before I left Rashid, his henchman had brought

in an ancient qawwâl, a bewildered old divine

whose sheep-like face had the blind look of one led to

the slaughter. I did not trouble his soul with any

onslaught on the secrets of his cult, for he was clearly

apprehensive, and we sat in amiable discourse which

gradually reassured him. Rashid told me aside that

the head qawwâl was more intelligent, and, after a little,

this personage too arrived. I suggested to the qawwâls

that perhaps they would honour me by a visit, so we

walked amicably down the village street to my little

house, where Mikhail prepared us tea. I began to

explain to Qawwal Sivu something of the purpose of

my visit, and then asked about the chants sung at the

spring feast and at burials, but as yet he was suspicious

and reticent. Their chants, he said with the air of

a trout whisking past a bait, were so secret and sacred

that no layman might know what they were; moreover,

he went on, "we ourselves do not write them

down. I learnt from my father and my son will learn

from me." We spoke of the seven angels,1 of whom

[25]

the chief is the Peacock Angel, and also of Shaikh ‘Adi,

who carries the souls of good Yazidis into Paradise on

his tray. Then we spoke of reincarnation, which is,

perhaps, the only positive form of belief which a Yazidi

holds. An evil man may be reincarnated as a horse,

a mule, or a donkey, to endure the blows which are the

lot of pack-animals, or may fall yet lower and enter the

body of a toad or scorpion. But the fate of most is to

be reincarnated into men's bodies, and of the good into

those of Yazidis.

|

1. M. Roger Lescot in his Enquête sur les Yézidis de Syrie et du Djebel Sindjâr (Beyrouth, 1938) complains mildly that the list of the seven varied with every person he questioned. I corroborate this. The truth is that on this subject, as on others, the Yazidis are beautifully vague. |

|

Two qawwâls at Baashika. [Qawwâl Sivu on the left.]

Here the arrival of the mukhtâr, the head man of the village, put an end to such talk and Mikhail brought another cup. The headman was a tall, well-built man, a landowner who farmed his own land with his sons, and his fairish face was, like many we saw in the village, of an almost Scandinavian type. These Yazidis wear their hair in a bushy shock beneath their red turbans, and the younger men often shave the beard, leaving the moustache long, or shave the face completely. I saw several who could have sat for portraits of Hengist or Horsa; others reminded me of the youths in Perugino's pictures. Older men let their beards grow. Amongst the children of the village some were as flaxen-fair and blue-eyed as Saxons.

The mukhtâr overwhelmed me with hospitable offers

of food. He offered to send me milk from his own

herd as long as I stayed, and begged me to let him know

if I needed anything. All our visitors left together

and Jiddan and I started for a walk, for he considered

it his duty to accompany me like my shadow. I turned

my face uphill, for it was good after living in a flat plain

to see grassy heights rising behind the village. These

foothills are about as high as the Chilterns, though

abrupt in gradient, and behind them the altitudes

rise until snow-hills are reached.

| |

|

We mounted past lime-kilns and juss2 pits on stony

[26]

and rocky paths where grass was scanty and the wild

flowers, mostly scarlet ranunculus, wild iris, anemones,

and campions, seemed the lovelier because of the sparseness

of the green. Young crops grew on the hillside,

wheat and barley, and here and there narrow stone

aqueducts led mountain springs down to the crops, the

kilns and the olive-groves. We climbed up until we

had a good view over the vast green plain which lies

between the hills and distant Mosul. In the midst of

it rose the mount of Tell Billa, looking just what it is,

a buried city. The Americans excavated it lately,

and it was Rashid who had been their right hand and

foreman during the excavations and was now responsible

for the watching of the site. From above, the

mound looked as if a large green counterpane had been

lightly thrown above the whole, and that if it were but

lifted, houses, fortress, and ramparts would appear intact.

Further along the plain rose Tepe Gaura, another buried

city, and beyond that again was Khorsabad, whence

lately two huge bulls had been unearthed and brought

down by lorry to adorn the new museum at Baghdad.

|

2. Juss is the Italian gesso, natural plaster. |

|

As for Baashika, just below, with its imposing new

church and tumble of flat-roofed houses, it looked like

a flock of sheep, huddling together for protection. The

white, fluted cones of Yazidi shrines rose out of the

olive-groves and crowned farther hills. On a grassy

knoll by the village I could descry a group of villagers,

and as I passed them on my way back I saw sitting

amongst them the village priest in his black robes and

tall hat. They were enjoying the evening sunshine.

| |

|

My first day at Baashika was over. I ate my supper

and went to bed betimes, falling into a refreshing sleep

which ended at dawn when I heard the scutter of hoofs

on the road outside as the flocks were led out of the

village to feed on the uplands. The spring air blew

sweet with herbs and flowers into our small courtyard

as I crossed it for breakfast, and I had hardly finished

[27]

before Rashid arrived. A shaikh of the clan of Shaikh Mand,

he said, was visiting the village with his daughter,

and they had brought snakes with them and were going

from house to house exhibiting their powers in return

for a small fee, so he had bidden them come to my house.

I had heard about the descendants of Shaikh Mand,

who claim to possess power over serpents and scorpions

and to be immune to their poison, and asked Rashid

if they really were what they claimed to be. He

assured me that they were, and that he had seen Jahera3

("Snake-Poison"), the small daughter of the shaikh,

handle unharmed a poisonous snake fresh from the

fields, and that the serpents they carried with them

had not had their fangs removed. "It has been

known," he conceded, "for a shaikh of that clan to die

from snakebite, but if this happens they say that he

was not a good man."

|

3. The "J" is soft, as in French "je". |

The shaikh of Shaikh Mand and his daughter "Snake-Poison.

Rashid added that the shaikhs of Shaikh Mand ate serpents raw and suffered no harm.

The shaikh and his little daughter now entered our

courtyard. Large serpents, one brown and one black, were

draped about the necks of the man and child,

their tails falling behind like fur boas worn years ago

by European women. The shaikh unwound the big

black snake from Jahera's neck, and it slithered along

in the sparse grass looking very evil indeed. It was

some five or six feet in length and its body two inches

or more in thickness. He caught it again, returned it

to the child and then displayed his own. I disbursed

an offering and then the shaikh and the ugly little girl

posed for their photographs, holding the snakes' flat

heads close to their lips.

| |

|

I wandered about the village, visiting the sacred trees

and some of the white cone shrines. I soon learnt that

all places of pilgrimage were called mazâr, the word

being applied indiscriminately to a tree, a tomb, a

[28]

cenotaph, a spring, a stone, or a cave. The name of

a shaikh may be given to several mazârs; for instance,

there is a "Shaikh Mand" at Bahzané and another at

Shaikh ‘Adi, and two "Shaikh Zendins" within easy

reach of each other, one a sacred stone and the other

a tomb-shrine. The name Shaikh Shams4 or Shaikh Shams-ad Din5

is not only given to the tomb-shrine at

Shaikh ‘Adi, but several flat rocks or enclosed spaces

on mountain-tops n Yazidi districts have that name.

Near Rashid's paternal house an ancient olive-tree,

enclosed by a low stone wall, just by a stream, is called

Sitt Nefisah, and between the villages of Baashika and

Bahzané a cone-shrine bears the same name. I could

never get a satisfactory explanation of these duplicate

and often triplicate shrines, but it was noticeable that

one might represent a spring, stream, sacred tree, cave,

or sacred stone, and the other be actually a tomb. As

for Sitt Nefisah, I asked for explanations, but all were

vague. The Lady Nefisah used to sit beneath the tree,

or, perhaps she had lived there, no one knew. But

every Tuesday and Thursday evening at sundown pious

hands never failed to place a votive wick saturated in

olive-oil into a cranny in the wall, its flickering light

lasting but a few minutes. Moreover, those suffering

from malaria6 come to it, scrape some sacred dust

from the small enclosure, and drink it in water, thinking

to be cured. By the same stream is another sacred

tree, called Faqir 'Ali. Indeed, most of the holy springs

and streams are coupled with a sacred tree, sometimes

more than one.7 Sacred trees are usually fruit-bearing

— the olive, fig, or mulberry.

|

4. Shaikh Sun. 5. Shaikh Sun-of-the-Faith. 6. himma mutheltha. 7. This recalls the sacred Aina u Sindirka of the Mandaeans, the mystical "Well and Palm-tree" which are explained by Mandaeans as representing the Female and Male principle respectively. In the Jebel Sinjar, however, according to Jiddan, there is a sacred spring without the sacred tree — Pira Hayi. |

|

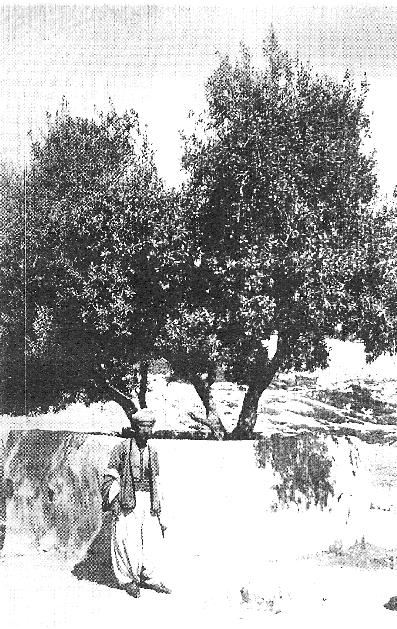

The sacred tree Faqir ‘Ali, with Tashid in the foreground.

Following the stream by the sacred trees up the valley where it wandered through beds of buttercups and oleander bushes — and one of the latter just below the imposing shrine of Melké Miran was hung with votive rags — I came, after crossing the stream more than once, to the upper washing-place known as Ras al-‘Ain. Jiddan remained modestly behind, for it is understood that if a man ventures near this pool in the morning he may surprise a bathing nymph. Several of the women who were beating their clothes on the stones by the pool were, actually, half-naked. Several of the girls were very handsome. The younger women wear caps of silver coins, one overlapping the other like scales; the turban wound around this cap is decorated with chains, and their heads, as they knelt to work, glittered from afar. Many wore beads, amber and scarlet, and long amulet-chains were suspended round their necks. The brides are always sumptuously dressed. One of the latter, a bold wench and far from comely, asked me to take her photograph and posed with her friend. I did as she asked, then she held out her hand for the picture.

"A bold wench ... asked me to take her photograph." I explained, and promised to send her the picture when it had been developed if she would give me her name, but she refused, sulkily, convinced that I was not telling the truth.

Returning to the village, I found that Rashid had

brought me a bunch of flowers, some from the hillside

and others from his own garden. Seeing me hunting

for something to put them in, he disappeared, to return

quickly with a glass from his house. Such charming

courtesy was characteristic of him. He came, he said,

excusing his call, to tell me that the midwife would

call on me that afternoon.

|

[30]

Chapter IV. BIRTH"Thy queen is Artemis, that lightens labour." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XXVII. The midwife arrived. She had several names, and was usually addressed as "Mama" or, more politely, Hajjia, but I named her mentally Sairey Gamp. She was old: her white hair straggled about her face in wisps and she was far from clean. She spoke in a husky, confidential voice, nudging me occasionally to emphasize a point, and her Arabic was so queer that I had to call in Jiddan to interpret into more familiar language. Here, as in Baghdad, women of the villages use words and expressions which one rarely hears from men. Jiddan was not in the least embarrassed by obstetrical details, nor were we. Luckily there is no prudery about such matters in the East. A woman may veil her face, but she will describe in fullest detail before her young sons the bringing-to-bed of a neighbour. | |

|

Mira Wansa had already told me a good deal about

the way in which Yazidi children come into the world,

and now the old woman added detail illustrated by

gesture and much dramatic comment. Birth was her

all: she was its priestess, standing at the portals of

life and death, and I fear that many must have gone

out of the world by the latter instead of coming in by

the former owing to her ministrations. A good deal

of what she and Mira Wansa told me I have put into

an appendix,1 for it may be useful to the anthropologist,

but weights my narrative unduly here.

|

1. Appendix B. |

|

[31]

Mira Wansa had told me that an expectant mother

should only look upon "good things". "If she sees

a snake or a toad, or an ugly thing, the child that is to

be born will be like them. I once knew a woman

whose baby was born with a head like a sheep, and the

mother told me it had happened because she had gazed

at a sheep."

Hajjia said that she was sent for when the labour pains began. The woman is usually hurried down to the cellar, which she is likely to share with goats, sheep, and fowls. The room is not crowded with women, but a mother, sister, and one or two female relatives may be present, and if possible, the "other sister". The woman does not lie for the birth but crouches, clinging to another woman, who comforts and encourages her, while the midwife massages her abdomen and squats behind ready to receive the child when it comes into the world. If labour is protracted, the midwife invokes supernatural help. "O Khatun Fakhra help her!This, said Hajjia, was what she chanted over her patient. Now Khidhr Elias is the prophet Elijah, and Shaikh Matti is Mar Matti, the Christian saint to whom the ancient monastery of that name is dedicated, but who was the Lady Fakhra? Both Jiddan and Hajjia hastened to inform me. She was the mother of holy shaikhs, Shaikhs Sajjaddin, Nasruddin, Fakhruddin, and Babaddin, and is the especial patroness of women in child-birth. After a safe delivery a thankoffering should be made in her name, and unleavened bread, a simple dough of flour, salt, and water called khubz fatîr, is baked and distributed to the poor. If the family is well to do, a sheep is killed and its meat added to the thankoffering. "If this is not done, she appears to them in dream and says to [32] them, 'Why have you not given to the poor in my name? I helped you and you have done nothing in return! ' "

"Shaikh Matti, thou with thine own hand help

me!" chanted Hajjia, returning again from the Yazidi

to the Christian saint. "That is what I pray over

them."

| |

| Another way of hastening the birth, she said, was to procure the gopâl (stick) of the Baba Shaikh, who always carries one, and to beat the woman with it gently seven times. When the child is born, the mother must remain in bed seven days. She is never left alone lest she see angels or demons in various shapes and go mad. A particular danger is an evil fairy, the Rashé Shebbé or Shevvé, who may substitute a changeling for the human child, or harm mother and babe. On the seventh day after birth the mother gets up, takes a hot bath and then goes with her friends to running water or a spring and throws in seven handfuls of seven grains boiled in water (like a bride), and then crosses the water and eats the porridge with her friends. A similar ceremony takes place when the child cuts its first tooth. The father names the child, and when he does so, usually slaughters a sheep, or a fowl, and distributes the meat. The name chosen is often that of a dead relation, a grandfather, parent, brother, or deceased child, and some think the new-born infant a reincarnation of the person after whom it is named.2 | 2. Mira Wansa told me this. She has discussed reincarnation with the shaikhs, and said that when she described a curious dream she had in which she was a soldier, the shaikh told her that she had probably seen a past life in dream. Formerly, when a person died, the kocheks claimed to have the power of foreseeing in a vision how the departed soul would incarnate, but when I spoke of this to Qawwal Sivu in Baashika, he denied it and said, somewhat naively, that the kocheks had given up their visions nowadays "because they are frightened of the Government". |

|

[33] When the child is forty days old, the shaikh comes to the house and cuts from its scalp two locks of hair, one for himself and the other for the pîr, and receives a present from the parents. No scissors must touch the child's head until this is done. [I noticed that Yazidi children have a wide bar shaved on the crown, from which bar another is shaved to each temple, the square of hair remaining being trimmed into a fringe which falls over the forehead.]

Shows how head is shaved. Hajjia promised that she would fetch me to assist at her next case. "I bring some thirty babes into this world each year in Baashika," she told me. I gave her some money and promised more if she kept her word.

Hajjia then told me of a trick that the Rashé Shevvê

had once played on her.

| |

| "I had delivered the woman," she said, "and was back at my house, which had no door to the courtyard. That night there came one shouting outside my room, 'Come, come! So-and-so is in labour!' Now this was the woman in whose arms I had laid a babe that very day, but, thinking perhaps that a twin child was to be born, I hurried out into the dark. I followed the figure, which was very tall — for you must know [34] that the Rashé Shevvé is very long, like the tantal,3 and it went before me and led me, not to the house, but outside the village! When I saw whither I was being taken, I was very afraid and ran and ran till I reached my own place. After that, khatûn, I had a door made to my house!" | 3. The tantal is a hobgoblin with the power of appearing immensely tall. |

|

* * * * * It was my duty to pay several calls. First, there were the official calls, and I drank tea by invitation one day with the mayor of the village and his comely wife, a girl of Mosul, a kind and hospitable pair. Then there was the schoolmaster. He was a widower with children, so it was his mother whom I visited. She was of a Baashika family and had taken over the task of bringing up his children when her daughter-in-law died in child-birth. She was a simple peasant woman herself, a Christian of the Latin persuasion, and a picture of the Pope hung on the wall. I liked her generous manner and smile, and thought the schoolmaster a lucky man to have such an excellent soul to look after his orphans. Then there was the Yazidi mukhtâr. I went one morning to return his call and found that he and all his family were out in the fields, hoeing onions, so returned later. They were expecting me and I was taken to a pleasant upper room, white-washed, its unglazed windows overlooking the olive-groves and the lovely green plain. It was reached in the usual Kurdish way by a steep outer stair unprotected by ledge or rail, upon which tiny children and kids clambered up and down. Rugs and cushions were spread for the guest, and the mukhtar and his friends sat round the room smoking long pipes with small clay bowls filled from capacious woollen tobacco bags, and discussing crops, prices, and [35] local politics. In this village, where there is neither radio nor newspaper, no telephone, telegraph or even daily post-car, the war only meant the increased price of certain commodities; the rest was mere polite inquiry for my benefit. "This Hitler — has he not yet made peace? By the power of Allah, he shall be brought low!" Or, sometimes, with a slight note of anxiety, "Khatûn, think you that the war will come here?" "If God wills, no," I made reply, and a fervent echo "Inshallah!" went round the room. With the Yazidis it is the host or his son who prepares tea or coffee for the guest, for it is a ceremonial gesture, not a household task relegated to women. I brought with me, as is my habit, a small bag of chocolates and sweets for the children, and these regarded me with shy favour from the doorway. I was on my way from the mukhtâr's house when I was waylaid in the street by a qawwâl whom I had not yet seen. He had a snub nose and a humorous face, and was to become a friend. "Khatûn," he said, "have you not yet been to see the American?" "The American?" I repeated, surprised. "Yes, there is an American missionary who lives down the hill — a good man; if you wish, I will take you to him." I shall never know whether it was the missionary who sent him or whether Qawwal Reshu acted on his own initiative, but I found myself presently admitted to the outer courtyard of a house by an Assyrian woman and led into an inner court, where a chair was placed for me. I learnt then that the missionary was not a real American, but an Assyrian trained by American missionaries. He appeared after an interval, during which he had donned the most European plus-fours I had seen for some time. As I happened to be speaking [36] Arabic, the conversation was begun in that language, although I was shamed to find out later that his English was fluent. He had the massive physique and strong features of the true-born Assyrian, and was both well-read and intelligent, in fact I enjoyed our talk. He told me several things that I wanted to know, while warning me that it was unlikely I should find out much for myself, as the Yazidis were bigoted and secretive to the highest degree, and would not admit a stranger to their ceremonies. I told him that I knew that, and that my only purpose in coming was to see as much as I could of the spring feast, and get to know the Yazidi women. In the afternoon I decided to go to the neighbouring village of Bahzané, for I had heard that a Yazidi shaikh, said to be skilled in magic, lived there in exile, and I wished to meet him. Jiddan and I set out. The road passes through crops of young wheat and beans in flower. On either side rise grassy hills and knolls crowned here and there with conical shrines, round which clustered a quantity of graves. Jiddan told me that Yazidis like to place a fluted cone over the grave of a young man or boy who has died after reaching puberty without being married, that is, he is treated as a saint provided that he is beloved and his family have the means to raise such a monument. The attitude of the Yazidis towards celibacy is curious and seems to suggest Christian influences. Shaikh ‘Adi never married, his brother is said to have created a son without the aid of a woman, and tradition says that other companions of the saint provided children for themselves in the same manner. I have often heard from Yazidis of a saint, "He was very pure: he never married", an attitude entirely opposed to Jewish and Mandaic ideas, for people of these races look upon an unmarried man as a sinner against Life. Most of the Yazidi graves are marked with a rough [37] stone placed at the foot and head, although here and there a tomb is wholly covered with masonry, or has an elaborate headstone bearing an inscription, local marble being used for the slab. The inscription usually states in Arabic that So-and-so passed into the mercy of God on such-and-such a date. All face east. A few are decorated with simple incised carvings: at the side of one I saw was a shaikh's gopâl (stick with a hooked handle), and rough representations of a dagger and powder-horn. We learnt afterwards that this dead shaikh had been stabbed to death. A stone saddle over another grave records that the departed died from a fall when riding. I have seen plaits of hair attached to headstones in these graveyards, for it is the custom of widows in their grief to cut off their hair and leave it on the tomb. The air bore sweetness from the hills, for these were covered with grass and flowers except where the rock crops through. Here and there were olive-trees, and groves, and gardens lay between the cultivation and the lower plain beyond. Storks paced about the field solemnly, rising and flapping their wings in slow flight when we came near. No one kills these privileged birds. Bahzané is built on a mound, and the houses, flat-roofed, clustered close together, with the green hills rolling right up to the walls. Here, too, there is absolute absence of rubbish, and no dead dogs or filth pollute the outskirts. The streets are so narrow that with arms extended one can almost touch the houses on either side, and three or four persons at most can walk abreast. They are roughly paved, with a rain-gutter down the centre, so that one can walk dry shod on either side. We skirted the village and kept to the outermost street. In the middle of the way rose a curious mortared hump, some four feet high, with a small opening in [38] front which showed within a flat sacred stone. The aperture was blackened by votive wicks. A passer-by told me that it was named Shaikh Zendin. Passing steeply downhill again and coming outside the village, we found ourselves at the celebrated shrine of Shakih Mand, which is lodged just where a narrow ravine above Bahzané debouches into the plain. A mountain stream flows through. the rocks and passes just above Shaikh Mand into the washing-pool at which the women of Bahzané beat their household linen. Shaikh Mand possesses its own sacred spring. Before the shrine is a small herb-grown courtyard enclosed by a low wall. Here I found the snake-eater, sitting with the four guardians of the tomb and other scarlet-turbanned Yazidis in a peaceful circle before the shrine conversing in low tones and smoking their qaliûns. We were invited to join them, but I passed first behind the white-washed building to lay, at the direction of one of the guardians, my small offering by the clear water which welled from the rock. Then I returned, and Jiddan and I sat awhile, glad to rest, whilst one of the men in the circle produced a lute he had made himself from the wood of a mulberry-tree. The wire strings were four in number, the keys at the top of the neck were like those of a guitar, but the low bridge slanted at an angle. Round sound-holes were bored in the lower part of the belly and also at the sides of the instrument. "We call it a tanbûr," they said, putting it into my hands. The lute player's pleasant music, at once intricate and primitive, mingled agreeably with the voices of the children playing and splashing at the pool above, where only a few women now lingered. The shrine of Shaikh Mand, Bahzane.

But we could not stay, and were directed to the

shaikh's house in the village. The shaikh, dark and

lean of countenance, greeted us politely when we

arrived and took us up to sit on his roof in the evening

sunshine, but it was plain that all was not well. We

[39]

soon learnt the cause of his distraction: his little girl

of four years old had fallen earlier in the day from

the roof upon a heap of rough stones in the courtyard.

As the roofs of Kurdish houses, used as sitting-rooms

and playgrounds, are rarely protected by a wall, it was

a matter of marvel to me that more children did not

fall from them. I was taken to the living-room where

the child lay on a bed covered with a quilt, motionless,

but alive. A mujebbir (bone-setter), they said, had told

them that no bones were broken. I begged them to

keep her quiet, but before we left the mother had

picked the little thing up and was carrying her

in her arms. It seemed impossible that the child should

survive. We left.

Chapter V. BAHZANÉ AND SHAIKH UBEKR"May spiders weave their delicate webs over martial gear, may none any more so much as name the cry of onset!" -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XVI. "KHATÛN! Will you speak to the chaûsh (sergeant) of the police? He is angry and says he will stay here no longer, and the other policemen want you to come and persuade him." It was Jiddan, with my servant Mikhail, who spoke, seeking me early the next morning. The police were our neighbours, and I knew the sturdy Kurdish sergeant, baked by many summer suns, as a most respectable man. As I went along, both explained what had happened. A Yazidi man had run off with a woman outside his caste, and the lives of both were in danger. They had fled for protection to the police, who counselled them to leave Baashika. The lovers were poor and could ill afford the car which the police subordinates, wanting to get to Mosul quickly for reasons of their own, tried to make them hire. The sergeant had taken the part of the eloping couple. "Wallah, my afrâd are not good men," he chided. "They will not obey me, and I shall resign." Close by sat the couple in the taxi summoned by the police. The men looked sheepish, when I did my best to reason with them, and declared that they had only one wish, and that was that the sergeant should not leave them. The matter was settled with ludicrous speed, the sergeant would stay "for your sake", the taxi was dismissed, and the couple escorted whither they wished. [41] I could not imagine why I had been called in at all; perhaps it was to witness the sergeant's impeccability, unless I had heard only a part of the story. I wanted to return that morning to Bahzané to inquire after the injured child. As we set out, Jiddan inquired diffidently whether I would turn aside a moment to visit the house of his shaikh? Jiddan is hereditarily attached to the clan of Shaikh Sajaddin, and on the night of our arrival he had eaten supper with them. That very morning, a shower having fallen during the night, I had seen a comely girl on the roof spreading out to dry the gay woollen rug in which Jiddan wrapped himself to sleep, and on asking who she was I heard that she was of the household of Jiddan's shaikh. Jiddan told me that his shaikh was in prison and that the old shaikha his mother, the women, and the children were exiled from the Sinjar and lived in Baashika. "What has your shaikh done?" "Khatûn, he had trouble when the law about conscription came in. He helped some Yazidis who escaped into Syria." Military service is an old grievance. It caused a rebellion most bloodily quelled in Turkish times before the Great War. The trouble was settled by certain concessions at the instance of Sir Henry Layard, the Assyriologist, through the mediation of the British Ambassador at the Porte. War is not actually contrary to the Yazidi creed, but close contact with infidel companions in arms, who eat foods that are polluting, and force the Yazidi to break his ritual laws, is abhorrent to them. The very dress of a soldier contravenes the faith, for a lay Yazidi wears a shirt with a wide collar cut loosely in front and fastened behind, and at prayer-time he lifts the hem of the neck to his lips. Accordingly, when the ‘Iraqi Government introduced conscription the Yazidis again showed opposition, and Bekr Sidqi, the general who murdered Jaafar Pasha and [42] was responsible for the Assyrian atrocities, quelled them with brutal severity. It was the religious leaders who were behind the resistance; some were hanged, others sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. The majority of the younger men now accept the situation, and it may be that the European war has done more than a little to convince them that a man can no longer live securely within his own religious and racial palisade. The shaikha lived near by. When I entered the courtyard she came forward to meet me, a frail but dignified figure clad in white cotton, a white woollen meyzar (a kind of toga) slung over her shoulder, and the white veil from her turban brought wimple-wise over her chin. Jiddan told me her name, Sitt Gulé. There were marks of poverty about the place, nevertheless tea was brewed for me, and they insisted that I should eat some mouthfuls of the paper-thin bread dipped in a bowl of cream and sugar, and a bowl of butter and sugar. The butter and cream were the products of their own cow, and were wholesome, though flies swarmed above them and a few of the cow's hairs were visible. One ignores such trifles, and I ate a mouthful or two and praised the flavour, watched by the shaikha, three younger women and eight children, two being babies in arms. I took leave when politeness permitted, and continued my way. Seen from the street: the courtyard of a Yazidi house, Bahzané.